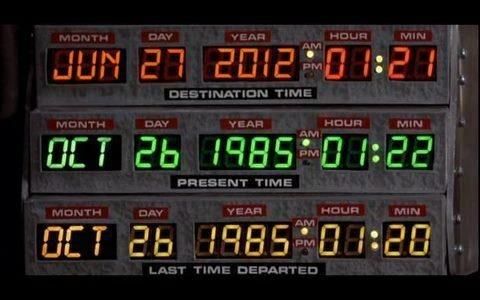

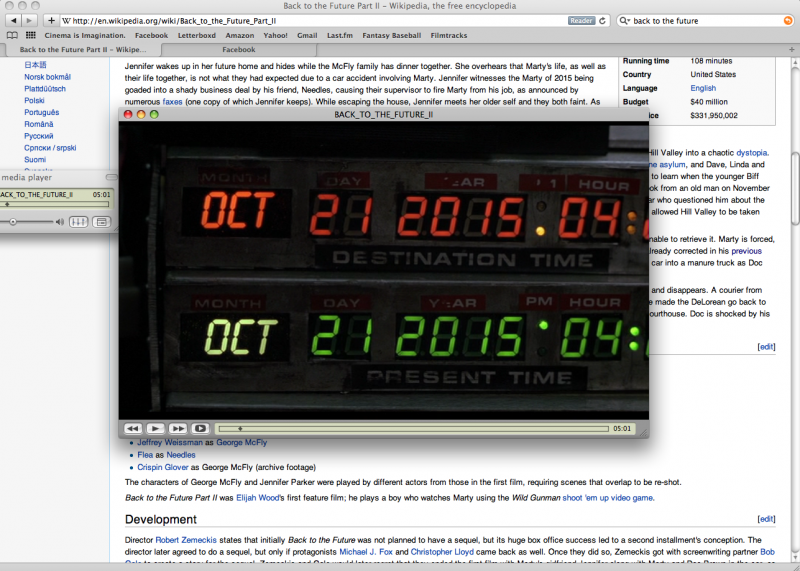

Here is the actual date: October 21, 2015. The good news: there's still time to develop hover boards.

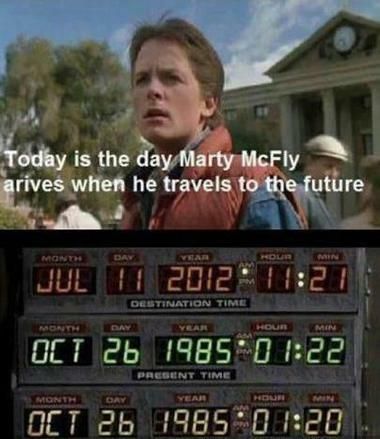

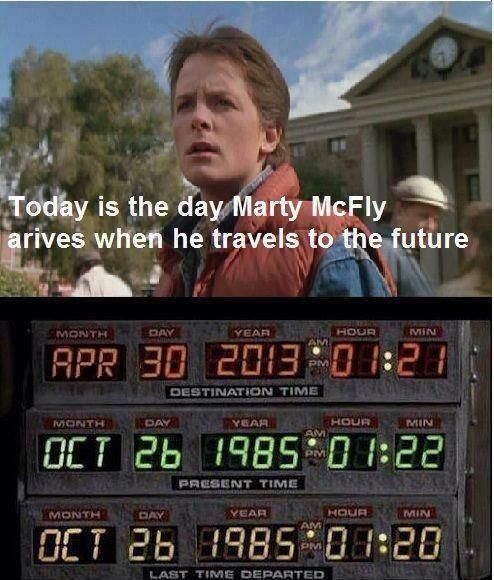

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

October 21, 2015

Social media is insistent, the date Marty McFly went to in Back to the Future II is today, whatever date today happens to be....

The Freedom of Capital: Milos Forman's Portrait of Larry Flynt

It is easy to embrace The People vs. Larry Flynt as a cinematic defense of freedom of speech or deride it as a botched biopic, but I think Milos Forman is smarter than both of those readings. The skeleton key for my understanding of Forman is in the obscure Soviet-era aesthetic stiob, which is a form of absurd humor that requires such an over-identification with the object of its parody that it is difficult to tell whether there is sincere support for the object, subtle ridicule or some strange mix of the two. The clearest practitioner of the form is Paul Verhoeven, though his is lived out in sci-fi movie structure (Total Recall) and genre gaudiness (Starship Troopers) that openly embraces the absurdity of its aesthetic (RoboCop). Forman, on the other hand, is a smuggler, embracing the more conventional structure of Hollywood pictures (Amadeus) and subverting them slyly through his depiction of off-kilter subjects (Man on the Moon). This has led to more universal acclaim for Forman among mainstream critics and an apathetic disinterest in Forman by many serious critics and cinephiles.

Monday, April 22, 2013

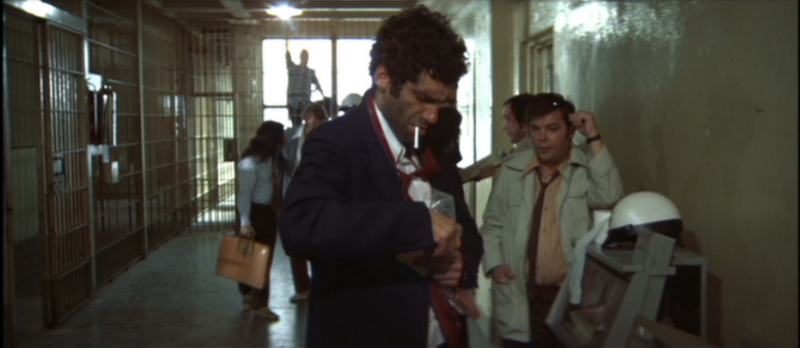

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Few people can do genre revisions like Robert Altman.

Probably because Altman doesn't really care either way; he's just making a film.

Underneath the palm trees and drug-induced hangover of the West Coast in the early 70's is a rotting corpse. Marlow just happens to still live there, like a fish permanently out of water that must now learn how to breathe in the air. He will, Altman suggests, by the end.

Mysteries are everywhere but the most pressing ones involve people and guns and money.

Lots of people ask questions.

Do they get the answers? I can't remember.

Marlow's cat. Marlow's neighbors.

Marlow's apartment building. Celebrity impersonation guard.

Altman includes these things and they become the fabric that is both essential and non-essential.

Narratively, they are not very important. Cinematically, they are what must be.

Altman has a way with those things.

By the end, we have witnessed the end of an era and the beginning of another.

A bit like McCabe & Mrs. Miller in that way, but slightly hopeful about the possibility of adaptation. Marlow has changed by the end.

He is simply tired of it all.

Tired of being used. Tired of allegations.

Tired of plots and subplots.

Tired of lies. Tired of distrust.

It may not feel radical, but it is.

And then there is that stare. The look on Marlow's face as he listens to Terry explain it all.

No epiphany; no a-ha moment.

Only the cold heart of man staring back at the walking dead.

film journal entry: 04.22.2013

Friday, April 19, 2013

1973 Cii Movie Awards

Top 10 Films of 1973

1. The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman)

2. Paper Moon (Peter Bogdanovich)

3. Electra Glide in Blue (William James Guercio)

4. Badlands (Terrence Malick)

5. Don't Look Now (Nicolas Roeg)

6. The Sting (George Roy Hill)

7. American Graffiti (George Lucas)

8. The Spirit of the Beehive (Victor Erice)

9. Westworld (Michael Crichton)

10. World on a Wire (Rainer Werner Fassbinder)

Honorable Mentions: Sleeper (Woody Allen), O Lucky Man! (Lindsay Anderson), Mean Streets (Martin Scorsese), Fantastic Planet (René Laloux), Charlotte's Web (Charles A. Nicholas & Iwao Takamoto), The Last Detail (Hal Ashby)

1. The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman)

2. Paper Moon (Peter Bogdanovich)

3. Electra Glide in Blue (William James Guercio)

4. Badlands (Terrence Malick)

5. Don't Look Now (Nicolas Roeg)

6. The Sting (George Roy Hill)

7. American Graffiti (George Lucas)

8. The Spirit of the Beehive (Victor Erice)

9. Westworld (Michael Crichton)

10. World on a Wire (Rainer Werner Fassbinder)

Honorable Mentions: Sleeper (Woody Allen), O Lucky Man! (Lindsay Anderson), Mean Streets (Martin Scorsese), Fantastic Planet (René Laloux), Charlotte's Web (Charles A. Nicholas & Iwao Takamoto), The Last Detail (Hal Ashby)

Labels:

1970s,

1973,

Alternate Oscars,

Awards List,

Cii Movie Awards,

George Lucas,

Nicolas Roeg,

Peter Bogdanovich,

Robert Altman,

Terrence Malick,

Top 10,

Victor Erice,

William James Guercio

American Buffalo (1996)

A fierce portrayal of working class greed and American entitlement. Dustin Hoffman and Dennis Franz are tremendous, finding the reality of their characters behind and through all the obscenities and Mametian turns of phrase. Hoffman is the Ratso Rizzo that didn't die on a bus on the way to Miami. Franz is more conflicted, trying to justify himself by maintaining an air of humanism while playing up his uncertainty.

Michael Corrente plays it cool, not "opening up" the stage play too much while also avoiding a collage of close-ups. It is foolish to pretend that the film is not just two people (sometimes three) talking to each other, so he stages the action well within the space and ends up saving his close-ups for the moments they are truly needed. Corrente may not be as bold in his camera placement as Mike Nichols in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (who is?), but he doesn't have to be. He crafts a swirling, claustrophobic film with two swirling, claustrophobic characters at its core.

Trapped within their pattern without ever talking about it -- they speak bigger than they are.

It needs to be stripped down and raw. Remove the artifice to get at what's real.

Business. Businessmen. Selling junk.

They would hate to miss something valuable.

They don't want to miss that margin of profit.

I like to imagine Mamet writing a companion piece to this, with two older ladies in a craft store.

American Wreath.

Hoffman has jumped in head first: always talking, always moving, always shifting, always blaming....

Is "Teach" an ironic nickname?

It's Donny who teaches. Bobby learns by example -- and it costs him.

Do what I say not as I do. Typical American attitude.

The storm may be coming but that only slows them down.

We can still get what we want. Maybe.

We need to be sure.

Loyalty is marketing. Brand image. A thing to cultivate in customers.

Do what you can to make what you can.

It doesn't have to be cutthroat to be damaging.

Main Street can be just as brutal as Wall Street.

Mamet thinks it is.

film journal entry: 04.19.2013

Thursday, April 18, 2013

Rounders (1998)

Gone are the days when I give a neo-noir a pass for simply being one, but I still like this film. Mostly for the performances, the way Edward Norton crawls under my skin, the way Damon seems so confident (is this the late-90's answer to the early-70's Redford?), the way Malkovich eats Oreos, the way Landau is so trusting.

Maybe it's all a little too perfectly clever. But that's okay.

It's a film about clever.

The narration is smart enough.

That smart narration kind of smart that confidently says what is really happening.

I might not buy it with a lesser bunch of actors. I might not buy any of it.

But that's why there are actors and that's why they command salaries.

The muted jazz score.

The wet city feeling.

It is all very uncomfortable.

I guess the troubling thing is how clever people can make such bad decisions.

film journal entry: 04.14.2013

Wednesday, April 17, 2013

1980 Cii Movie Awards

This list and awards compiled March 15, 2013.

For the criteria of choosing the awards, click here.

Top 10 Films of 1980

1. American Gigolo (Paul Schrader)

2. Melvin and Howard (Jonathan Demme)

3. Berlin Alexanderplatz (Rainer Werner Fassbinder)

4. Raging Bull (Martin Scorsese)

5. Bad Timing (Nicolas Roeg)

6. 'Breaker' Morant (Bruce Beresford)

7. The Changeling (Peter Medak)

8. Stardust Memories (Woody Allen)

9. Kagemusha (Akira Kurosawa)

10. Popeye (Robert Altman)

Honorable Mentions: Coal Miner's Daughter (Michael Apted), Spetters (Paul Verhoeven), Poto and Cabengo (Jean-Pierre Gorin), Mon Oncle D'Amerique (Alain Resnais), Airplane! (Jim Abrahams, David Zucker & Jerry Zucker), Heaven's Gate (Michael Cimino)

Judging Oscar: 1973

I have watched or re-watched the films nominated for Best Picture and Best Director and then placed a value judgment on what I saw cinematically. Last time I did 1980. This is 1973.

WINNER: The Sting (dir. George Roy Hill)

BEST PICTURE

WINNER: The Sting (dir. George Roy Hill)

Charm and entertainment

value can go a long way, and why shouldn’t it? This is a perfectly executed update and expansion of the

Depression-era programmer that has as much fun with its scenery as it does with

its plot. And I won’t hold any of

that against it. Snappy dialogue, scenery-chewing

performances, period costumes, a wonderfully evocative ragtime score. David S. Ward's script is sharp and sparkling, perfectly structured and paced and kept that way by George Roy Hill. It is impossible for me to view this

film objectively anyway, as it was the first “grown up movie” that my parents

let me see (at around 13 or 14 I was determined to see any Oscar nominees I

could from the 70’s through the 90’s).

I loved it then, even as it spun my head around in circles, and I love

it now for Robert Shaw, for Paul Newman, for all the bit character actors like

Durning and Gould. I love it for the sets, for the feeling, for the nostalgia. I love it for the plot mechanics. I could sit

down and watch it just about any time.

I don’t have to figure it out; I like going along for the ride.

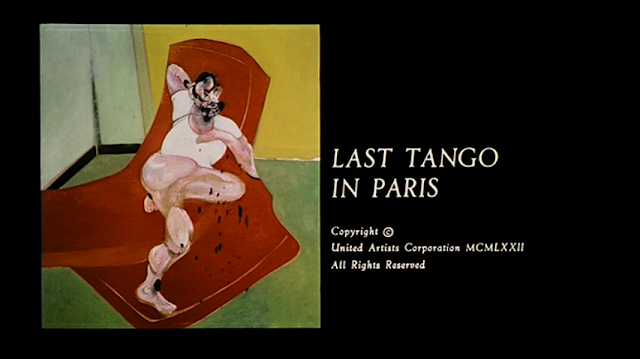

Last Tango in Paris (1972)

What does it take to truly know another human being?

Are human beings even knowable at all?

Do we get to a point where everything we think we know is thrown out the window and we start all over again at square one?

This film has been read a variety of ways, some highlighting the sex, some highlighting the emotion, some highlighting the performances, some highlight death. Depending on what a critic wants to talk about, they will highlight that portion at the expense of the rest and end up misreading the film. Maybe we're all misreading it. Even Bertolucci, who calls the film a romance, which to me is ludicrous.

The sex of the film is circumstantial, a by product -- though an essential by-product. Brando's character wants to strip a portion of his life down to a primeval essence, doing away with names and history in favor of raw sexuality and unblocked emotion. Eventually, the past of the characters cannot but infringe on the purity of silence because the past both justifies and contradicts every reason they have for being in that room. If sex is anything it is the brief physical union of two human beings and because of that, it can't simply be isolated like a math problem on the blackboard. It always comes with people attached, people with names and places and histories and fears and desires beyond the physical.

Brando's Paul says he doesn't want to be named except by a grunt or a groan, but human beings don't speak in grunts and groans. Maybe that's what he hates about life. He wishes he could get to some imagined reality where language doesn't matter anymore. But he can't stop talking.

Is it true, what he says? Is it fantasy? Does it matter?

She is about to be married and is making a film with her fiance about their life together and her personal history. She is bored by it. Her fiance's camera is an ineffective way to understand her. She volunteers stories and thoughts to Paul who dismisses them. He isn't interested in history, he doesn't care where she's been. In the midst of these close relationships she is alone. Why does she feel the need to talk about those things? She can't help it. She just does.

She subverts easy explanations. The truly liberated woman, freed from the responsibility of justifying herself. But no one is truly free; no free person can go very far before constructing barriers again.

So we return to the first question: are human beings knowable?

I don't think so. That's the tragedy of this world.

The opening shot of the film is a Francis Bacon painting taking up half the frame. A man sits reclined on a couch. He seems hollow. Maybe he's being analyzed. Maybe he's just reclining. Either way, his face seems broken and demonic, his exposed thighs bulge into each other without clear definition. Paint splatters across the front of him, not in the painting but on the painting.

The brutal psychology.

I can't justify everything that happens in the film or everything said, but I can't look away either. Bertolucci has crafted a fascinating film regardless of perceived faults that prove themselves to be strengths if viewed in the right framework.

That, to me, is the strength of great art.

film journal entry: 04.17.2013

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Two-Lane Blacktop (1971)

Two-Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman, 1971)

Does this film really exist?

Where is the pride, the pretense, the artificiality?

First dialogue is 6 minutes in.

The success is two-fold: silence and ellipses.

The silence comprises a major part of the film.

Action or non-action -- the background is usually moving.

Dialogue is sparse yet conversational. Not overly stylized.

There is an openness, a willingness to let action and decisions take place off-screen.

Conversely, thoughts and indecision happen on-screen.

When the Girl arrives, she simply gets in the car.

No scene is made because the characters honestly do not care.

They will take her along. Sure. Why not?

When she leaves, she simply up and leaves.

Independent. Unbounded. The open road.

Warren Oates embodies a real person we see in parts.

A lying iceberg who must talk continually.

If he stops talking, he dies.

Sweaters. Gloves. Lilted smile.

Show me a better character in American cinema.

The allowance is for the audience. Watch and listen.

Play along. Follow the lines. Embrace the characters.

This land is our land, every corner of it.

The widescreen mirrors the landscape.

We see the whole thing.

film journal entry: 07.09.2012

Does this film really exist?

Where is the pride, the pretense, the artificiality?

First dialogue is 6 minutes in.

The success is two-fold: silence and ellipses.

The silence comprises a major part of the film.

Action or non-action -- the background is usually moving.

Dialogue is sparse yet conversational. Not overly stylized.

There is an openness, a willingness to let action and decisions take place off-screen.

Conversely, thoughts and indecision happen on-screen.

When the Girl arrives, she simply gets in the car.

No scene is made because the characters honestly do not care.

They will take her along. Sure. Why not?

When she leaves, she simply up and leaves.

Independent. Unbounded. The open road.

Warren Oates embodies a real person we see in parts.

A lying iceberg who must talk continually.

If he stops talking, he dies.

Sweaters. Gloves. Lilted smile.

Show me a better character in American cinema.

The allowance is for the audience. Watch and listen.

Play along. Follow the lines. Embrace the characters.

This land is our land, every corner of it.

The widescreen mirrors the landscape.

We see the whole thing.

film journal entry: 07.09.2012

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Street of Shame (1956)

The last film of Kenji Mizoguchi is a subject they say he liked. There is a human interest in the lives of the women -- they are all in debt unless they embezzle. Slowly descending spirals, some a little more rapid. In the same way athletes only have a few good "peak years of production" while their bodies are young, so too the women of Tokyo's Yoshiwara district.

Western egalitarianism creeps in. Morality that had been held in check by family tradition and name is now losing ground and must build external constraints. Government intervention. Suicide seems easy, logical even. Life only gets harder.

A son disowns his mother. Humiliation.

Things change. Uncertainty.

Settle into life's groove. Where are the good patterns?

The unfortunate tune is always ringing.

Use people, charge interest.

There is no stopping you.

More melodrama than Ozu, who always askewed it. Embraced in part, allowed utterance.

The lonely bins collect the crazies.

What will stop a man from beating a double-crossing woman?

Mickey brings irreverence. Reality.

A shocking scene with her father.

Building slowly to a boiling point.

She knows him better than he does, see through him, finds the hollowness in his resolutions and desires.

A businessman wants respectability. Otherwise, he is unconcerned.

During the daytime it is a quiet anystreet.

At night, the neon lights up, the girls are out front.

Is there a new Tokyo underneath it all?

film journal entry: 07.09.2012

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

American Graffiti (1973)

American Graffiti (George Lucas, 1973)

George Lucas---what happened to you? Remember when you cared? Remember when you effectively placed boomer nostalgia within a humanistic context that was both funny and interesting?

It finds the angst, insecurity, distractions and hormones of high school and gives us great characters to follow as they amble through a night on the verge of summertime in Modesto.

Paul La Mat. Candy Clark. Both are tops.

Harrison Ford is always cool, even when he's too old for high school, too old to be on the proving grounds with his souped up automobile.

Lucas doesn't end it with nostalgia, which takes it from good movie to great movie, with the epilogue description of what happened to the four main males after school, to the "now" (the now of 1973, I suppose).

The eternal now.

Dead, lost, writer, insurance.

There you have it: the American Dream.

Leave your mark on the landscape. Be remembered.

Was that night important? Was it essential in the course of things? Only in its unimportance.

Only in the way it isn't about epiphanies.

As the future dawns behind the car at the end, it is the small choices that make up a life.

We see that. They lived it. They lived through it.

Are they any better?

Is this one more thing they will forget?

Is this the embarrassment they think of when they remember their youth?

film journal entry: 04.05.2013

George Lucas---what happened to you? Remember when you cared? Remember when you effectively placed boomer nostalgia within a humanistic context that was both funny and interesting?

It finds the angst, insecurity, distractions and hormones of high school and gives us great characters to follow as they amble through a night on the verge of summertime in Modesto.

Paul La Mat. Candy Clark. Both are tops.

Harrison Ford is always cool, even when he's too old for high school, too old to be on the proving grounds with his souped up automobile.

Lucas doesn't end it with nostalgia, which takes it from good movie to great movie, with the epilogue description of what happened to the four main males after school, to the "now" (the now of 1973, I suppose).

The eternal now.

Dead, lost, writer, insurance.

There you have it: the American Dream.

Leave your mark on the landscape. Be remembered.

Was that night important? Was it essential in the course of things? Only in its unimportance.

Only in the way it isn't about epiphanies.

As the future dawns behind the car at the end, it is the small choices that make up a life.

We see that. They lived it. They lived through it.

Are they any better?

Is this one more thing they will forget?

Is this the embarrassment they think of when they remember their youth?

film journal entry: 04.05.2013

Monday, April 8, 2013

Blue Velvet (1986)

Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

I've seen Blue Velvet several times and the thing that strikes me about it this time is Lynch's fascination with human beings. Not simply their dark, sinful substrata, but their violence, their nïaveté, their curiosity, their fatalism.

I wouldn't call Lynch a fatalist, but he is fascinated by the inevitability of some people's choices, their preoccupation with things that are harmful, even fatal to them.

Dennis Hopper frighteningly lives there. It is his most strikingly honest performance, maybe because he always lived there, even as he pushes realism out the door in favor of broadstroke menace and subdued chaos.

I would like to think the obviously mechanical robin could be real, but no. The mechanical bird is the only kind of bird that can conquer the type of darkness Lynch shows us. It is the only solution he can muster.

Fabrication. Art. Reorganized nature.

Maybe Lynch is a fatalist after all.

film journal entry: 06.30.2012

I've seen Blue Velvet several times and the thing that strikes me about it this time is Lynch's fascination with human beings. Not simply their dark, sinful substrata, but their violence, their nïaveté, their curiosity, their fatalism.

I wouldn't call Lynch a fatalist, but he is fascinated by the inevitability of some people's choices, their preoccupation with things that are harmful, even fatal to them.

Dennis Hopper frighteningly lives there. It is his most strikingly honest performance, maybe because he always lived there, even as he pushes realism out the door in favor of broadstroke menace and subdued chaos.

I would like to think the obviously mechanical robin could be real, but no. The mechanical bird is the only kind of bird that can conquer the type of darkness Lynch shows us. It is the only solution he can muster.

Fabrication. Art. Reorganized nature.

Maybe Lynch is a fatalist after all.

film journal entry: 06.30.2012

Them! (1953)

Them! (Gordon Douglas, 1953)

Atomic age sci-fi is usually smarter than audiences in a post-Mystery Science Theater 2000 mediascape give them credit for and Them! is smarter than most atomic age sci-fi. Taking the approach of exploratory film film rather than battle film, it maintains intellectual credibility through tiny details (gas masks, geography, acknowledgement of countries and governments besides the USA) and hides the creatures until much later into the film. The struggle is not to believe that giant ants exist but to figure out where they're hiding.

The detective maps are spread thin, but finally, "we'll let you know when he's well" is what they tell the psycho ward of the guy who saw ant-like UFOs. She's the token smart woman but she doesn't fall in love this time, light affection, perhaps, but it was the 50's in LA...

Clever performances.

James Whitmore gives his life without fanfare.

The scientist is older and a little out-of-the-age-of-machines.

No hesitation to study for science.

No loyalties to biology.

He understands that danger awaits research, despite fascination.

Beautiful black-and-white cinematography -- shocking red and blue title on top of a B&W desert.

Notes of doom and forboding -- the atom bomb bring unknown futures in itself and its effects.

Carefulness and curiosity.

Several Wilhelm screams.

film journal entry: 07.09.2012

Thursday, April 4, 2013

Films are about emotions...

|

| Roger Ebert speaks to an audience in Savannah, GA in 2004, during his 3-part scene-by-scene analysis of Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941). I am in attendance (though not pictured). |

Roger Ebert (1942-2013)

I'm flipping back through The Great Movies after hearing about the passing of Roger Ebert. It was a book that introduced me to a bunch of (now obvious) classics/favorites -- Aguirre the Wrath of God, McCabe & Mrs Miller, A Hard Day's Night, A Woman Under the Influence, Manhattan, Sweet Smell of Success -- while also letting me know it was okay to love Oliver Stone's JFK, to seek out a copy of Hoop Dreams, and to immerse myself in the generally held canon of world film classics while not feeling beholden to it.

In his essay on JFK, Ebert recounts an argument Walter Cronkite had with him after Ebert had praised the film: "I am a film critic and my assignment is different than his. He wants facts. I want moods, tones, fears, imaginings, whims, speculations, nightmares. As a general principle, I believe films are the wrong medium for facts. Facts belong in print. Films are about emotions."

I have gone back and forth on my opinion of JFK over the years, just as I have on Roger Ebert. The Great Movies seems so obvious to me now, so canonical. Yet, I do remember a time when I didn't know there was a film director named Werner Herzog who was making extraordinary films and I didn't know Robert Altman wasn't the obvious answer for best American filmmaker of the 1970's. Ebert was an essential voice. I read his reviews and would be pushed to think more deeply about the films he rated favorably if they left me more cold, challenged to defend (to myself) the movies I liked that left him cold. When I was reading him regularly in the late 90's, his top 10 lists often championed films that were not being championed by other critics (Eve's Bayou, Dark City) and pushed me to branch out and see what unchampioned works I could find on the fringe.

As cynical as I could be, it is obvious to me that he really did love the movies he wrote about in The Great Movies. There are plenty of canonical classics he left out, several "unsuspecting" films he brought in. And ultimately he did what a great film writer or critic should do: he made me want to watch films. He helped me engage with and understand some difficult works, helped me articulate what I responded to and strongly disliked in movies and helped fuel a passion to take in and enjoy the diversity of the medium fro mall over the world. So, I could dismiss him as populist (as I have done in the past). He worked for a major newspaper. So what? I would take one Ebert essay over a thousand Armond Whites and their forced contrarianism. I could dismiss him as sometimes having shallow observations. So what? He was engaging a broader audience and has written about hundreds of movies over the course of his life.

But I come back to that quote. "Films are about emotions." I didn't understand that much when I read it then, I'm sure. But it is where I live now. It is why I loved JFK when I couldn't reconcile all that JFK said or seemed to say. It is why I still love JFK. And Herzog. And Altman. And McElwee.

At the end of the day, Roger Ebert helped me love film more. Beyond me, he was a formidable voice to a generation of film viewers who were given a video store full of cinema history and didn't know what to do with it all. I can only hope there is someone who, in an age of irony and cynicism, can stand in his place and passionately entice future generations to seek out the old paths and to love the medium for what it is, not what it symbolizes.

Goodbye, old friend.

PS: I still need to see Last Year at Marienbad, Lawrence of Arabia, Pandora's Box and The "Up" Series. After that, I will have seen all The Great Movies.

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

A Metaphor: King Kong (2005)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)