BEST PICTURE

WINNER: Platoon (Oliver Stone, 1986)

Stone takes the WWII movie

and puts it in Vietnam. There are

a couple of decent setpieces but overall, I don’t find anything particularly

noteworthy about it apart from this being the only major Vietnam movie that was

directed by an actual Vietnam veteran.

Willem Dafoe and Tom Berenger are very good as the dueling Sergeants

with differing philosophies of warfare and leadership, and that dynamic really

is the most gripping part of the film.

This comes to a head in the film’s best scene: a tiny farming village

where the distrustful GI barge in and begin to emotionally and, later,

physically torture several South Vietnamese civilians because they are believed

to be untrustworthy in their association with a battalion of Vietcong. Led by the malicious Sgt. Barnes

(Berenger), even Chris Taylor (Sheen) gets in on the hostilities before Sgt.

Elias (Dafoe) steps in and puts an end to the madness. It is a good scene and Stone certainly

doesn’t shy away from some of the other secret realities of the war (drug use,

racism, classism, disenchantment, distrust of authority), but it also doesn’t

add up to much more than a slightly interesting shrug. Thankfully, this is before Stone got

swept away with his fractured patchwork aesthetic of the 90’s, so the film actually

maintains a consistent point-of-view and shows some understanding of screen

geography, even if it lacks the associative power of his post-JFK work.

Children of a Lesser God (Randa Haines, 1986)

A really stunning film for

its frankness, Children of a Lesser God,

at several points, had all the makings of either a bad teacher/savior film or a

bad TV movie of the week.

Thankfully, Randa Haines remained focused upon the characters, whatever

journey the story took.

William Hurt and Marlee Matlin give astonishing performances, not only

charismatic but open in a way uncommon for an on-screen romance. We see many seasons in this

relationship and thankfully all involved (Matlin, Haines and the writers) are

honest about the challenges inherent in relationships as well as the

additional challenges in a relationship between hearing and deaf partners. Though it doesn’t take any chances in

its aesthetic, you have to respect a film that treats its subject with such

humanity and honesty.

Hannah and Her Sisters (Woody Allen, 1986)

Woody builds a very

charmingly structured film that deals with the lingering tensions within the

artistic children of two actor parents in Manhattan. His observations on human insecurity and the confusion of

desire are quite poignant and, as usual, Allen has cast his film

extraordinarily well. Dianne Weist

and Barbara Hershey are particularly wonderful, but even Allen’s neurotic

hypochondriac is self-reflexively hilarious and existentially fascinating. The film is built with such supreme

confidence in the actors carrying the emotional weight required that it all

appears effortless and graceful.

And any film that has Max von Sydow as an aging, disenchanted artist who

complains about the contrivances and paradoxes of modern life is worth watching. This is a film that deserves its good reputation as a showcase of everything Woody Allen does well.

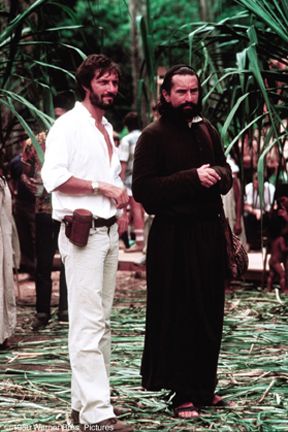

The Mission (Roland Joffé, 1986)

Speaking of showcases, this is one to the opposite. The Mission is an absolute

terrible mess of a film. The story

of Jesuits fighting politically against the claims of the Spanish crown in the

jungles of South America could be fascinating if Joffé wasn’t so distracted the

whole time. He seems so consumed

with saying something important that

he completely overlooks crafting any character that is a real human being. This is a particular crime when the

major theme of your film is the inherent value of humanity, regardless of

upbringing or ethnicity. Irons and

De Niro star in the film but are pretty nondescript. The narrative is so frustratingly contrived that I have no idea who could have responded to this movie with

such admiration as to nominate it. If one even searches for deeper abstract meaning, the politics and theology are so uncertain and muddled that there is absolutely nothing to like about this film except the beauty of the jungle, which is clearly not enough to sustain a 2 hour running time.

A Room with a View (James Ivory, 1985)

What starts out rather

insufferably moves into the realm of droll, under-the-surface comedy once the

action leaves Florence for the English countryside. A Room with a View is less a comedy of

manners than I had feared going in and instead proves to be a surprisingly potent rip on the Edwardian

leisure class. Full of good

performances (apart from the limited Julian Sands, whose charisma as a leading

man is completely assumed by the narrative) Helena Bonham Carter finds her

footing as a young woman wandering aimlessly through the amusements set before

her, Maggie Smith is her conservative chaperone, Denholm Elliot is a tactless

tourist and Simon Callow is quite charming as a totally ineffectual

priest. But, it is a young Daniel

Day-Lewis who steals every scene he’s in, playing Cecil Vyse as a hilariously

posh sophisticate who is engaged to Carter’s character throughout most of the

film, though he seems to love nothing except the feeling of being intelligently cultured. James Ivory isn’t as

concerned with the narrative as he is in giving an atmosphere of the time

period -- that perhaps keeps this from being better -- but overall it works.

MY PICK: Hannah and Her Sisters

I suppose it's not a surprise for the Academy to go with an important feeling war movie while Woody Allen is easily taken for granted for making a fascinating examination of the Manhattan art class. It just seems like Stone's film should be saying something important because he reminds you at every turn that what he's doing is immensely pressing, but 27 years later, I would rather sit down again with Woody's intelligent comedy and true human insight than Stone's overblown "the war was in us, man" self-importance.

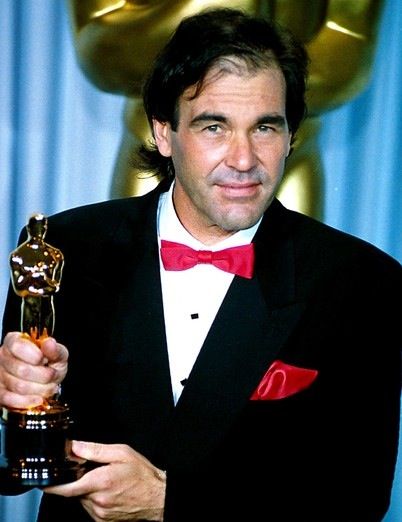

BEST DIRECTOR

WINNER: Oliver Stone (Platoon)

Never one for subtlety,

Oliver Stone loves to build things big and loud and brash. Dealing with wartime themes, that tact

mostly works. What doesn’t work is

when Stone gets a little too on-the-nose philosophically, like the final

narration that laughably states “we did not fight the enemy, we fought

ourselves.” I say laughable

because it completely disregards the increased masochism that Chris Taylor

embraces as the film progresses.

He isn’t fighting himself, never was. Further, the film can’t dismiss Chris’ descent into

war-induced madness as a “casualty of war” and at the same time judge so

harshly Sgt. Barnes’ commitment to madness because they both have to spring

from the same root. Still, Stone

is able to pepper the film with a number of true-life details of rookie GI

(ants, overstuffing backpack, naivety) and he orders his aesthetic reasonably

well. Nothing earth-shattering,

just solid continuity and form.

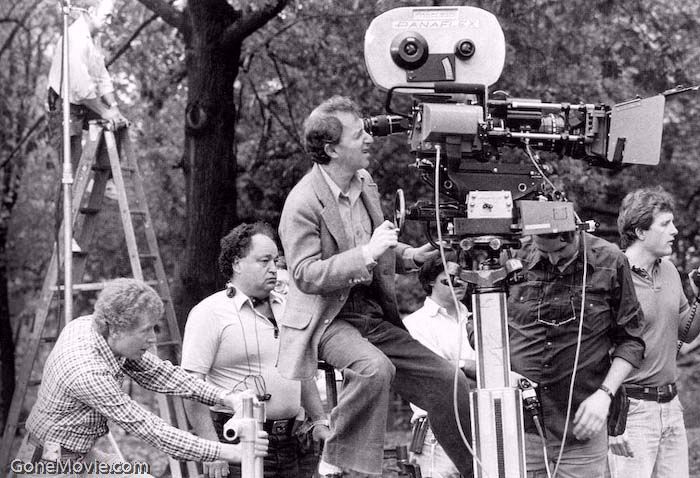

Woody Allen (Hannah and Her Sisters)

Separating Woody Allen

the director from Woody Allen the writer may be difficult to do sometimes, but

this strikes me as a particularly careful and honest effort by the director in

realizing his own fantastic script.

Using careful composition and a striking level of editing restraint and

intent, Allen builds a character-driven story that reaches just as deep as it

sets out to while still feeling alive with possibilities. He knows when to hold a shot, when to

get out of a scene, when to stay on a reaction, when to bring in music and what

music to use. His economy of form is extremely impressive here, having taken enough Bergman to heart to finally give us a film that realizes the full potential of that lingering influence.

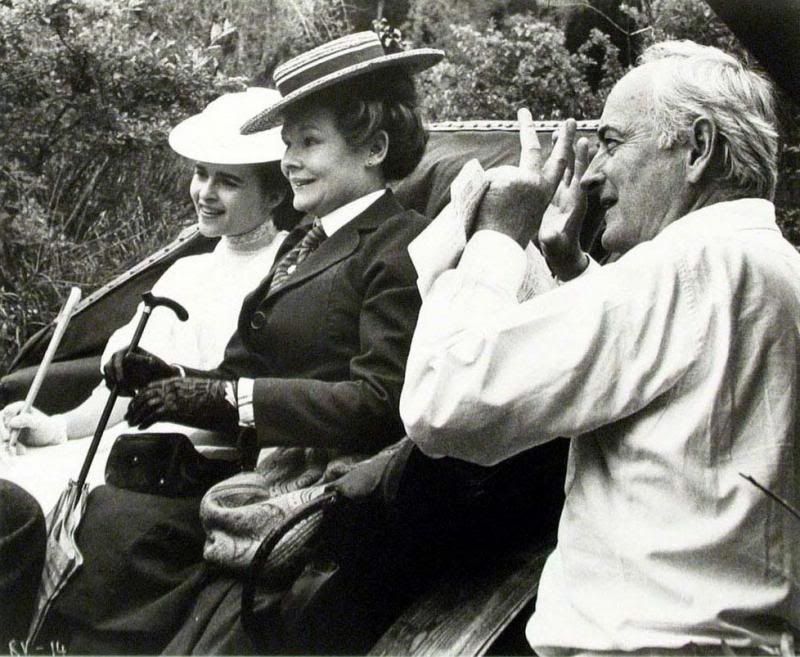

James Ivory (A Room with a View)

Building an immersive world

is difficult for any film director but it only becomes more difficult the

further that world is removed from the present context. To Ivory’s credit, he is able to evoke

early 1900’s England without noticeable effort. He fills the film with good character actors and finds them

interesting business while on-screen. The most

glaring mistake here is the utterly uninteresting primary love interest. George is played by Julian Sands with

such blandness that it feels as if it must be a further commentary on the

shallowness of the leisure class.

But, Ivory has a lightness of touch that keeps the whole affair from

becoming bogged down in heavy-handed examinations of fate and love, happy to

explore its subject with droll humor and nuanced inflection.

Roland Joffé (The Mission)

Joffé is so distracted by

the mountains that he forgets the fundamental task of creating interest in the

people climbing them. The camera

is always in the wrong place, the emotional beats are always off, the obvious

is overstated, the ambiguous remains so, and the musical score is ready to tell

us of the underlying beauty and wonder of the humans we barely know or care

about. Chris Menges gives a

serviceable attempt at epic photography, but in the end, it is all for

nothing. The waste of talent and

locations in this film is staggering.

David Lynch (Blue Velvet)

Nearly a full 20 years

before Todd Haynes ever made Far From Heaven, Lynch had already made Haynes’ more obvious

vamping of Douglas Sirk irrelevant with this artistic masterwork. David Lynch takes the naïve yet curious

protagonists and has them uproot something buried deep in the heart of small

town America. It isn’t just an

indictment of hidden sin; Lynch’s film digs much deeper. He is curious to watch the human

preoccupation with the harmful, the deadly; he watches how someone can give

themselves to the pursuit of being baffled by the darkness just outside of

their view. They just want to know

how it turns out, even though it seems so obvious. Lynch has carefully manicured his landscape toward the bold

and bright; he is likewise fascinated by the clearly fabricated. People speak with a voice that is a

little too stilted, strangers are a little too nice, yet the villains fascinate

us with their untapped vileness.

This film deftly shifts tones between gothic humor and absurd nightmare

and ends up as one of the more unique cinematic experiences of the 1980’s. This is the film that where Lynch

ascended from being an interesting curiosity to a legitimate filmic artist and Blue Velvet is still one of his best films.

MY PICK: David Lynch

I'm surprised the Academy had the vision to even nominate Lynch for director, as Blue Velvet was uncertainly received by critics. Even Dennis Hopper, giving one of the essential performances from the decade, failed to receive attention for Blue Velvet and had to get his 1986 supporting nomination via Hoosiers. It's a shame the Academy whiffed on an opportunity to nominate their first female director in Randa Haines and her very sure work, instead opting for the critically bloated Joffé. While I'm at it, I'll go ahead and call James Cameron's Aliens the 1986 war movie that deals most essentially and entertainingly with everything Stone dabbles with in Platoon, but Oscar has never considered sci-fi an important enough genre to give its top awards. From what is nominated, it is a close call between Woody Allen and Lynch but I go with Lynch because, as much as I enjoy Hannah, I find Blue Velvet to be more essential, expressive and unique.

MY PICK: David Lynch

I'm surprised the Academy had the vision to even nominate Lynch for director, as Blue Velvet was uncertainly received by critics. Even Dennis Hopper, giving one of the essential performances from the decade, failed to receive attention for Blue Velvet and had to get his 1986 supporting nomination via Hoosiers. It's a shame the Academy whiffed on an opportunity to nominate their first female director in Randa Haines and her very sure work, instead opting for the critically bloated Joffé. While I'm at it, I'll go ahead and call James Cameron's Aliens the 1986 war movie that deals most essentially and entertainingly with everything Stone dabbles with in Platoon, but Oscar has never considered sci-fi an important enough genre to give its top awards. From what is nominated, it is a close call between Woody Allen and Lynch but I go with Lynch because, as much as I enjoy Hannah, I find Blue Velvet to be more essential, expressive and unique.

No comments:

Post a Comment