BEST PICTURE

WINNER: One Flew

Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

(Milos Forman, 1975)

One of the quintessential anti-establishment pictures, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is able to capture the frustration, rage and bewilderment of being trapped in a system that seems to be a benefit only to realize that walls and bars are not so bad: it is the people who smile calmly at you while taking everything from you that should terrify us most. It is wonderfully written and performed while Haskell Wexler’s cinematography tries its hardest to avoid shadows inside the hospital, lighting everything as evenly as possible until we get to those night scenes. Avoiding the pat functionality of every character “representing something,” Forman is able to carefully chart the growing relationships within the group of patients and how their awareness of the world and each other is slowly affecting them. Forman also maintains a consistent point-of-view, never leaving the patients to present the world outside the hospital or in the doctor’s conferences. This not only endears us to the patients (and McMurphy in particular), but also adds to our growing frustration as we see the institution seemingly create some of the diseases it offers to cure.

One of the quintessential anti-establishment pictures, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is able to capture the frustration, rage and bewilderment of being trapped in a system that seems to be a benefit only to realize that walls and bars are not so bad: it is the people who smile calmly at you while taking everything from you that should terrify us most. It is wonderfully written and performed while Haskell Wexler’s cinematography tries its hardest to avoid shadows inside the hospital, lighting everything as evenly as possible until we get to those night scenes. Avoiding the pat functionality of every character “representing something,” Forman is able to carefully chart the growing relationships within the group of patients and how their awareness of the world and each other is slowly affecting them. Forman also maintains a consistent point-of-view, never leaving the patients to present the world outside the hospital or in the doctor’s conferences. This not only endears us to the patients (and McMurphy in particular), but also adds to our growing frustration as we see the institution seemingly create some of the diseases it offers to cure.

A wonderfully dry, flat,

perfectly manicured costume drama that deflates the pretensions common to the

genre by laying everything out on an even philosophical plane and avoiding the

standard issue melodramatic moments in the service of higher, and in many ways

self-reflexive, interests. Barry

Lyndon tells the story of the

rise and fall of an Irish nobody, a gambler who will both find and lose a

fortune over the course of the film.

I am not giving anything away because the narrator and the title cards

are all-too-quick to remove suspense, allowing the audience an opportunity to

embrace the characters on their own, forcing us to find the empathy in the

human species.

Cold is a term often used to describe Kubrick in general and Barry

Lyndon in particular, but the

coldness of the treatment of the characters is subverted by the warmth of the

color schemes, especially those nighttime interiors lit only by the orange glow

of candlelight. It is complex in

the way the narration counters the visuals, the way the genre expectations are

subverted, the way Kubrick’s philosophy of human depravity is shown within such

regal settings. Additionally, it

is impossible not to find dry humor in every facet of the film, as if Dr.

Strangelove had been slowed down

20 times and allowed to play at snail’s speed and we encouraged to laugh at its

slowness. The film is beautiful to

look at but even that is undermined by the reality of the characters on the

screen, Barry himself being as passive as a protagonist can be. Kubrick’s films are known for their

precision and careful craftsmanship, and here, he utilizes it all in the

consideration of fate and free will, the human drive, and the evolution of the

species trapped within prisons of their own making.

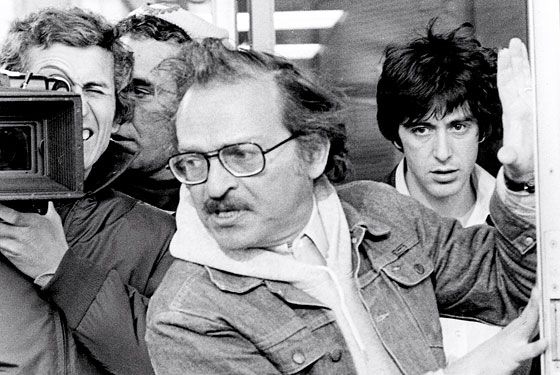

This is the kind of

actor’s dream project that seemed to happen over and over in the 70’s, a movie full of

rich characterizations and deeply conflicted motives. Al Pacino and Chris Sarandon were nominated for their performances

(which are wonderful), but it is John Cazale, the unheralded chameleon, whose

pitiable insecurity was the best expression of what it means to be powerlessly

at war against the system and even finding himself ultimately a follower in this tiny revolution. Cazale fills the screen with such pathos that one can’t help but feel sorry for the guy

even while Sal's carelessness seems to be undermining the whole

thing. Lumet plays the whole thing very cool, displaying his realist sensibilities in the service of narrative spark and raw emotion. Pacino gives everything he's got and it is this gut-wrenching

desperation that makes the film so genuinely affecting.

Hollywood’s first major

blockbuster is a movie that justly packed the seats in its day. Spielberg cleverly takes the monster

movie premise, sticks a character drama in the midst of it while taking some

cues from Hitchcock about how to ratchet up the suspense through camera

movement, editing and a fantastic John Williams score that doesn’t sound too

far removed from Bernard Herrmann’s work in Psycho. Not that any of this is formulaic, because it isn’t. Due to technical issues with the shark, Spielberg avoids showing too much of the monster, allowing the threat of danger to speak more potently than the sight of it and thereby proving what made Hitchcock a master of suspense (also proving how the limited technology of this era often proves better cinematically than the digital universes of CGI). The shark stuff aside, Spielberg’s interest in the main

characters provides a rich underlying subtext of male fear and insecurity that

is played out in the boat and on the beach, with Roy Scheider, Richard

Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw all giving fantastic performances. It’s too bad the Academy skipped over

Spielberg for a nomination, because it is pretty obvious that his design and

vision led to the film’s success.

If more contemporary blockbusters were like Jaws, critics of mainstream cinema would have far less to complain about.

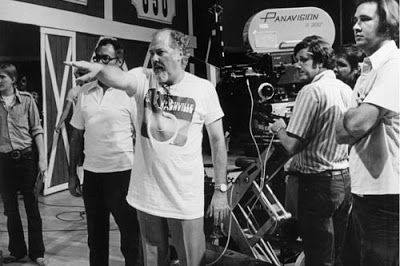

Nashville (Robert Altman, 1975)

There is a short list

that always comes to my mind when someone asks me to name my favorite movie of

all time, and Nashville is

always on it. What can I say? Nashville is as funny, complex, strange and haunting as

any film ever made. It isn’t really a

story and I don’t know how much it accurately captures Nashville, Tennessee in

the 1970’s, but the atmosphere it does create is something few films have ever

approached. There is a

smoke-stained longing that permeates the film: the fragile edges of talent

being tightly guarded by the overbearing, the overblown pride of place and name

being the cloak of insecurity and anemic imagination, the pompous wild-eyed

dreamer trying to pull meaning from monotony, the exploited failure returning

from the exploitation just as clueless as before, the gentle wanderings that

prove the desire to be loved is the secret hope of the sacrificial, the

ruthless conniving of artistry, the charm that belies the velvet dagger’s

thrust. It

is not just the actors – as brilliant as they are – it is the full-bodied

characters that are living within and without the frame. No matter where you look there is life

and interest. And it is not just

the characters – as rich and interesting as they are – it is Altman’s

willingness to pick them out in a crowd, to focus in on their particular story

of that particular moment, as mundane as it may seem. It

ambles through like someone at a party, finding conversations halfway through,

running into people at different spots and spending a few moments before

passing on and meeting again. But

it is not directionless. It is all

moving toward a singular moment: a moment of grandeur and tragedy, a moment of

pathos and rebirth. The symbolism

is no longer symbolism. It is

living and breathing and cutting.

There was no symbolism. It

was literal. It meant it. Every word and breath. Fame, fortune, politics, death, war,

music, and show business all find equal footing on the front steps of the

Parthenon.

MY PICK: Nashville

One of the best bunch of

Oscar nominees in the history of the award but I go with my heart and one of

the most inspiring films I know, a movie I’ve watched a dozen times and still

find it just as compelling as when it first hit me. I can’t fault the Academy with their choice, however, as Cuckoo’s Nest is a very good summation of what was so

good about this period in American mainstream filmmaking. And if I were not to pick Nashville, I would be hard pressed but it is a close call between Barry Lyndon and Jaws.

BEST DIRECTOR

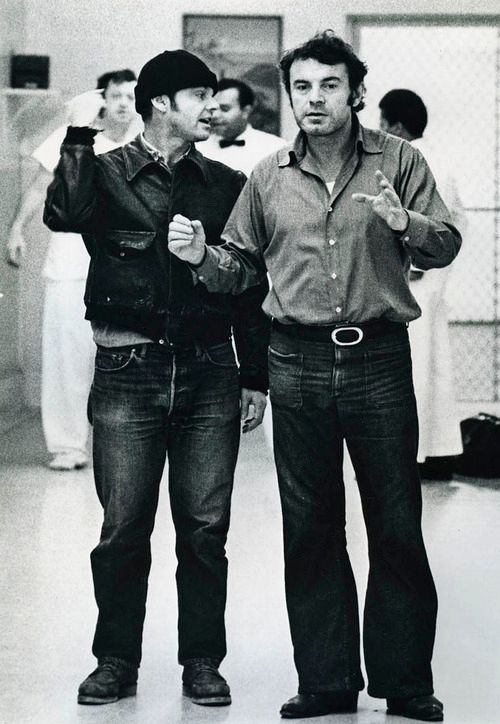

Milos Forman quickly

takes to his new filmmaking home in his second American film, finding not only

the more obvious totalitarian subtexts, but also the fascinating allegorical

strains relating to medication, perception, silence and marginalization. Jack Nicholson was in top form

throughout the decade and could carry any picture, but it is still astonishing

to see the atomic charisma and bravado he singlehandedly displays in this film. Of course, there is the now forgotten Louise Fletcher,

who is brilliantly miscast, perfectly embodying Nurse Ratched with a deadpan gentleness

that is as soothing as it is frightening.

Through her, Forman is able to both humanize and dehumanize the entire

institution, her subtle responses to the forceful threat of McMurphy being the

barometer for institutional tolerance of dissident behavior. By the time we realize exactly where

the film is going, Forman also has the courage to point the way through the

walls.

Typically overrated

during the 60's and 70’s, Fellini gained broad American interest by being one of the

most immediately recognizable European directors on the world stage. Known for crafting vaguely

surrealistic, broadly comic films with autobiolgraphical hints recognizable by

their carnivalistic atmosphere and unique casting, Amarcord exemplifies everything anyone could want in a

Fellini film. The question really

is whether or not one wants a Fellini film? Personally, I have never completely engaged with Fellini

beyond his ubiquitious 8½ (1963),

finding his forays into autobiography simultaneously bland and overblown: bland

in its narrative and emotional impact, overblown in its stylistic

conceits. There are a couple of

unforgettable images but overall, painting the rise of fascism in Italy as a

coming-of-age story of lustful youth is a little too cute for my taste. I’m not sure why the Academy finally

got around to this in 1975, considering it premiered the US in 1974 (and

premiered in Italy in 1973), but that seems to be the story with Oscar's honoring of European cinema in the 70's.

If Altman deconstructed

the movie musical in Nashville,

lending credibility and naturalism to it all by planting the songs within a

real world environment, Kubrick certainly deconstructs the period drama, down

to its very foundation in a similar naturalist bent. Not to say that Kubrick is seeking naturalism, because he has a rigorously formal approach to image-making, but the physical stuff the the film (costumes, sets, music, makeup) all comes with a naturalistic conceit that will then be turned on its head by the photography. John Alcott’s zoom lenses are used to flatten the dense

natural and manicured landscapes into massive barely moving paintings, while

his utilization of a specialized ultra-fast lens photographs the

interior night scenes exclusively lit with candlelight. Kubrick takes the affable screen

presence of Ryan O’Neal and turns him into a windup toy, a bland, passive

presence that is central to the philosophical intent of the picture. It is such a supremely odd film,

because Kubrick’s restraint even holds back some of his own elaborate

pretensions, though it is all in service of his exploration of individualism

and fate. And even with the avoidance of conventional genre trappings,

Kubrick’s insistence of building his highly manicured world only with the stuff

of the era (lighting interiors exclusively by windows or candles, for example)

lends the film historic credibility, though the narration puts the film very

specifically within a 19th century literary context. One could easily argue this is Kubrick's best film and the greatest confluence of all his philosophical and aesthetic concerns.

It is a shock to me when

I re-watch Dog Day Afternoon

and realize it is in color: it always felt like a bleak, black-and-white film

to me and that’s strangely how I seem to remember it. Lumet embraces a no-nonsense approach, both to narrative

development and to aesthetic, stripping away any notes of external beauty and

allowing the film to be a simmering pulse of raw emotion. His color palette is a series of browns

and grays, so the feeling of a black-and-white movie is clearly by design. He navigates the tension between the

rising threat of the police outside and the growing uncertainty of the

situation inside, and yet is able to show us enough in Pacino and Cazale to

empathize with their plight, even while they disrupt society for their own

purposes.

MY PICK: Robert

Altman (Nashville)

It is again close between Robert Altman and Stanley Kubrick, but Altman is what inspires me the most nowadays, though I have a respect for Kubrick and his accomplishment. In the end I find Altman's approach and final result more overall impactful. Also, I would have included Spielberg in the mix over Fellini's tiring lite-surrealism. The Academy went with Forman, a director whom I greatly love and respect (and who would win a second Oscar in 1984 for Amadeus) and whose great accomplishments as a cinematic subversive I think have been largely misunderstood (ie. The People vs. Larry Flynt ). I have noticed that even many critics these days see Cuckoo's Nest as being too one note, missing some of the interesting subtexts Forman has embedded within the film.

No comments:

Post a Comment