It seems like every problem I had with Dillinger (John Milius, 1973) is effortlessly overcome in Thieves Like Us, even though they are very different films with different intentions. The bank robbers in Altman’s film are not famous but they do gain recognition that eventually hinders their ability to operate. The seeds of envy will be sown as Elmo begins to be frustrated with recognition the young Bowie receives in the papers. They see how myths are woven to add pizzazz and fear for readers but they aren't intelligent enough to understand it. It just confuses them. When the paper nicknames him Elmo "Tommy Gun" Mobley, Elmo confesses: "I only had a machine gun once in my life. I didn't even get to fire it. I just...held it."

|

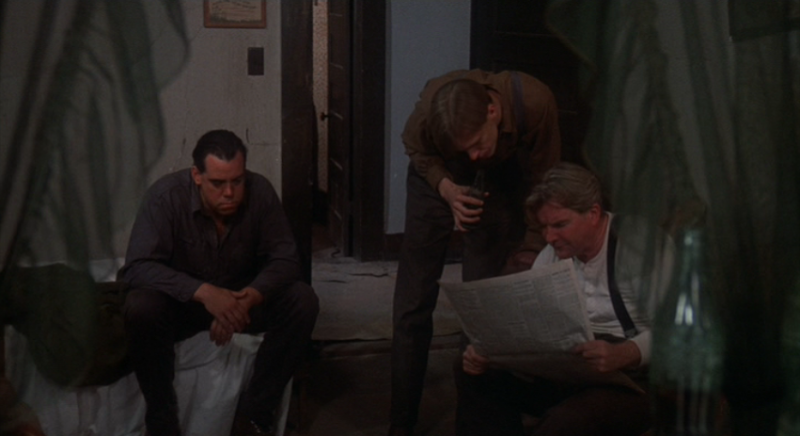

| T-Dub reads what the paper says about their jailbreak. "Not a whole lot about us, is there?" But the myths are there to justify their eventual violent downfall. |

|

| There are moments of such strange pathos and naturalism, as when a nervous Bowie talks to a stray dog to try and calm himself down. |

The radio is omnipresent, adding a thick atmosphere where fantasy and reality are strangely on an equal plane, where the pursuit of the robbers seems nearly as detached as the adventures of The Shadow. It also works as a unifying device similar to the loudspeakers in M*A*S*H. (The radio becomes a winking commentary in Bowie and Keechie’s love scene.) There is pathos and humor in Altman’s human universe, and those two are often inter-woven. I love the scene where Bowie misses his rendezvous because he couldn’t tell if the pickup at the crossroads was flashing his lights (as planned) or if they were simply shorting out. It is the sort of plain, uneventful human misunderstanding that most movies simply don't have the time for.

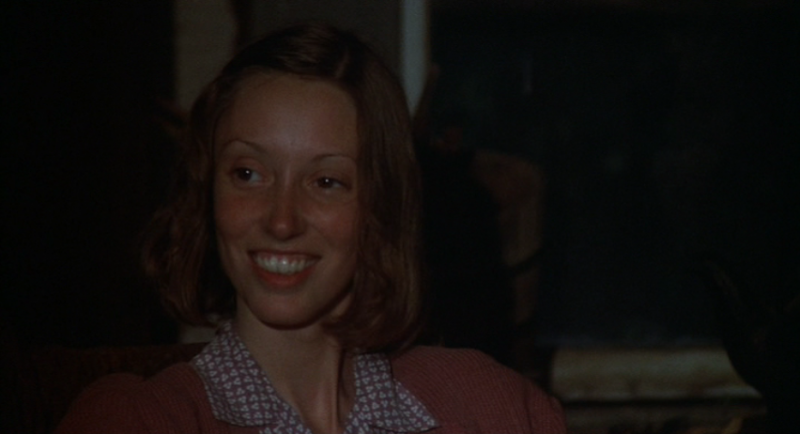

Shelley Duvall was always best in Altman's films. Somehow he knew best how to use her unique physicality and off-kilter vocal delivery, her natural quirk and charm. She fills the roll of Keechie with such naïveté and longing, but a determined acceptance of her lot in life that makes her far from passive. It is easy to see why Bowie falls for her. There is a sweet and unassuming nature to her that Duvall plays perfectly. The early scene with the two of them flirting on the porch, remembering growing up is so honest and revealing as they try and hide behind their stories. John Schuck, Bert Remsen and Keith Carradine are all great too with their naturalistic rapport. Three people who could only have met in prison and thereby have a strange union that even they don't completely understand. "They've never seen three like us," T-Dub exclaims. But does he really believe that or just tell himself that to add dignity and uniqueness to their otherwise working class existence?

Then there is that strange phrase that pops up from time to time: "people like us" or "thieves like us." It sets the robbers, in their minds, in a category by themselves, a group with a special purpose, personality and function that can only be properly understood by other people like them. Altman lets them talk that way, but spends his whole movie presenting them as sad and a bit lost. It's hard not to see this also as a fairly apt comment on the American South. For Altman, what makes them extraordinary is in just how ordinary they are.

No comments:

Post a Comment