Coming to audiences near the beginning of the New Hollywood era (1967-1979), Alex in Wonderland is both an appreciation of the artistic freedom afforded to directors by producers/studios during that time and a unique representation of the paradoxes and paralysis facing the New Hollywood filmmaker in light of that freedom. It is bold and audacious and brilliant, written and directed by Paul Mazursky, one of the forgotten dual talents of that era.

Thursday, June 20, 2013

Alex in Wonderland (1970) and the New Hollywood Paradox

Coming to audiences near the beginning of the New Hollywood era (1967-1979), Alex in Wonderland is both an appreciation of the artistic freedom afforded to directors by producers/studios during that time and a unique representation of the paradoxes and paralysis facing the New Hollywood filmmaker in light of that freedom. It is bold and audacious and brilliant, written and directed by Paul Mazursky, one of the forgotten dual talents of that era.

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

The Refusal of Culpability in 'Flight' (2012)

No one likes to take responsibility for the bad things that happen. It is easiest to blame someone else. We accept accolades for success but always shift the blame for the failures. If that is true of individuals it is just as true of the institutions we build. Families, governments, corporations, schools, even churches. It is the root of social diseases ranging from extraneous litigation to alcoholism. In that way, Flight is pertinent and hard-hitting. Not just because it deals with alcohol addiction, but because it deals with the root of addiction: the refusal of culpability. And, even though it paints a far-reaching societal portrait, it is also bold enough to admit that there is a way beyond it.

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

The Color Wheel (2011)

There is a moment about a third of the way into The Color Wheel where Colin's thoughts toward his sister are summarized in the statement, "You've always been a hot commodity in the world of perverts." Not that his insults are one-sided, as the entire relationship of this brother and sister is based on their annoyance with one-another and the ability to place uniquely searing insults at the feet of the other. Colin lambasts J.R. mostly for her failed dreams of being a news anchor and her taste in men (most recently illustrated in her affair with a broadcasting professor); J.R. lambasts Colin for his apathy and lack of imagination. But, as the story unfolds, it turns out that J.R. and Colin -- as cruel as they are to one another -- are only slightly less cruel than the world of their fairly privileged bubble.

Friday, June 14, 2013

The Spider's Stratagem (1970)

Movement through time and space.

Tiny movements, barely discernible.

The decisions made in a moment. The people who made them. The reasons don't matter.

The son of a hero comes home. He mirrors his father.

The same name, the same look.

Athos Magnani.

There is his old mistress.

There is the memorial.

There are his old friends.

There are the memories.

There are the lies.

Where does one end and the other being?

The son walks in all the same corridors, fields and roads.

He may be looking for closure. Closure is an abstraction.

Railways eventually covered over by grass. Single, sharp parallel lines eventually broken by the convergence of thousand askew lines, all for their own purposes.

Bertolucci builds slowly, allowing these movements to linger.

Clarity is not his end goal.

Literary allusions.

Fascism and anti-fascism (of course).

Reality and illusion.

Sometimes, the invisible men.

There is the oppressive realization that truth is good for some but the masses need the illusion, they crave it. The symbolic pointing to something great outside themselves.

The corporate imagination.

film journal entry: 06.14.2013

Thursday, June 13, 2013

The Death of Romanticism in 'Les Bonnes Femmes' (1960)

Swinging the pendulum deftly between various moods -- documentary-like observation, gender comedy, absurd comedy, tragedy and finally, quiet transcendence -- Chabrol's film shows a careful narrative structure and a formal beauty that really gripped me. This is my first Chabrol film and I come to it already familiar, though not overly enamored, with the other early touchstones of the French New Wave: The 400 Blows (Francois Truffaut, 1959) and Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960). This is a really beautiful and unique film that is made so rich mostly because Chabrol's keen interest in human interaction, spoken and unspoken.

A delicate portrait of city women and a searing subversion of romanticism, Chabrol follows four Parisian girls in their early 20's over the course of a handful of days and nights, though it is the stories of Jane and Jacqueline that get the lion's share of the focus. Both of these women are intensely romantic, though in opposite ways. Jane embraces the romanticism of choice, freedom, being unencumbered, being her own woman; Jacqueline embraces the more conventional romanticism of being swept off her feet by a man who loves her deeply. Over the course of the film, their romantic notions will be thwarted as the men who drift through their lives upend their dreams of freedom and love.

Jacqueline and Jane are walking home one evening when they are suddenly stalked very persistently by the ostentatiously lighthearted duo of Marcel and Albert. They are nothing more than guys looking for a good time and though they seem charming and entertaining early on, over the course of the evening they become increasingly callous and demanding of Jane, who is far more accommodating than Jacqueline. Eventually, she is in their apartment and expected to be sexually involved with both men. Chabrol, though ultimately sympathetic to the women who are at the mercy of men in power, still sees a paradoxical conflict where Jane's own freedom of choice has brought her to this compromised state. When Jane returns to her apartment early the next morning, we get the unfortunate feeling that she had to involuntarily give into at least some of the men's demands. She is not in the mood to discuss with her roommate anything that happened.

One of the key scenes is the night at the swimming pool, a scene where every major character (apart from Mr. Balin) is present. It starts as a lighthearted jaunt that slowly turns into a aggressive assault of masculine dominance in its good and bad forms. Marcel and Albert happen to be at the pool too, where Jane, Jacqueline and the rest are enjoying their evening. The two men quickly start teasing Jane into introducing them to their party and find that she has become significantly less accommodating since the last time she was with them. Quickly, things deviate into a prankish show of disapproval, where Marcel and Albert throw all the others into the pool and start dunking them all under water. Jane and Jacqueline obviously get the brunt of the dunking in what has quickly shifted from good-natured prank into psychological torture. Chabrol notes this shift in tone by shifting his camera angle, showing us underwater shots of Jacqueline being pushed under, matched with muffled underwater audio. Finally, we get our relief in the form of Andre, who dives in from the high dive to swim over and rescue Jacqueline from her peril. The two men, now emasculated and embarrassed, back off as Andre becomes the hero of the scene and the wish fulfillment of Jacqueline, who has noticed him stalking her recently.

At this point, it seems Chabrol has brought us full-circle into a traditional (though slightly unconventional) romantic film, as Andre and Jacqueline are quickly away into the countryside, sharing a meal together where Andre proves himself to be a jokester himself, full of little tricks that amuse the enamored girl. He takes them on a walk in the woods that slowly becomes more and more uncomfortable, until finally we are given an ambiguous moment of consummation, as the two lay together in an isolated area as the birds around them call out rhythmically. Chabrol finally lets us in on what is happening (having alluded to it so obviously earlier with Andre's own inquisition -- though as a hopeful optimistic, I disregarded it) as we see that Andre is strangling Jacqueline, whose squirms were not the happy writhing of passion but the desperate movements of anguish.

Andre leaves the scene quite hurriedly and we are never afforded an answer to his mystery. Why was he following her? Why did he want to kill her? Did he know anything about her at all? Instead, Chabrol takes us into a dance hall where a young woman is being asked to dance by a young man. We cannot see the man's face because we are left with the gaze of the young woman, who literally locks eyes with us and is intercut with the slowly changing angle of the glistening mirror ball above them. The metaphorical fractured beauty of the ball is now a frustrated thing, not giving us narrative or sentimental satisfaction, but a vignetted series of dots that clutter the atmosphere and highlight how bright the light could be if it were just focused. The romanticism that seemed so certain only ten minutes prior has now been unfairly shattered, and we are left with a moment to ponder the frustrating reversal as we experienced the fulfillment of our greatest fears rather than our greatest dreams. It is a strange moment of transcendence.

Monday, June 10, 2013

A Guide to Tex Avery -- The Walter Lantz Years (1954-1955)

Tex Avery left MGM in 1954 (though several cartoons he had already made for them would be released all the way up to 1957) to enjoy a very brief stint at Walter Lantz Productions. WLP were independently producing cartoons that were distributed through Universal Studios. Avery seemed to adapt to his new home very quickly, though he didn't stay long, and unfortunately left to never again return to animate short films. His animation style changed a little to reflect his new home and the changing landscape of the mid-50's, but the madcap antics, creative gags and self-reflexive humor remained in tact.

I watched these in chronological order and have written out a few remarks for all of them. All of these are fun and definitely worth watching. My particular recommendations will be highlighted in red.

See also: Tex Avery at MGM -- Part II (1950-1957)

Tex Avery at Walter Lantz Productions (1954-1955)

Avery definitely takes a different stylistic approach with the character animation in this first Lantz short, adopting a much more angular rendering of his subjects. Absurdity is still rampant and even though the final reversal is pretty obvious, it was funny to see.

Avery has a new character to play with and has some fun subverting his normal routine. Here, Chilly Willy (the cold penguin) is trying to sneak into a coat warehouse to steal furs while the knowing watchdog displays a restrained ability to undo everything Willy tries to accomplish. The fun of the cartoon is the power play dynamic between the dog and penguin and not the full on torture one inflicts on the other (as was Avery’s norm). A pleasant cartoon.

What begins as a retread of Deputy Droopy with a mix of I’m Cold turns into a really funny expression of cartoon immutability. A guard dog is keeping watch over a supply of fish while a hungry polar bear must overcome the extra obstacles added by Chilly Willy to avoid having the dog bite him. Thankfully, Avery keeps things fresh by adding some wonderful gags, including a scorcher with a clarinet. The final reversal takes a surprisingly sentimental turn, as the dog and polar bear are not able to live without each other.

A really brilliant premise for a cartoon, that basically takes the playful approach to loudness and silence from Rock-a-Bye Bear and Deputy Droopy and flips them with the character inside the room being unable to stop the noises outside. Here, the character has been traumatized by trombone music and his doctor sends him away to a special silent resort for peace and quiet. Naturally, his hotel neighbor turns out to be a trombone player who cannot be stopped despite the character’s best efforts that become more and more loud and always backfire. A fantastic twist at the end leads to the character’s literal disintegration. This is essentially Avery’s last cartoon (though imdb lists the two CinemaScopes as 1956 and 1957) and I find it to be wonderfully inventive, proof to me that had Avery continued animating shorts (even at Lantz), he would have still been able to produce quality cartoons with clever gags and premises.

Saturday, June 8, 2013

A Guide to Tex Avery -- The MGM Years, Part II (1950-1957)

I love Tex Avery and consider him to be one of the great animators. Though beginning his career in the 1930's, his creative high period is certainly during his time at MGM (beginning in 1941). Most critics cite his 1940's films as the most inventive and consistent while overlooking many of the masterpieces and other gems he created during the 1950's. Due to Warner Brothers' indifference (the current rights-holders of the lion's share of Avery's output) in presenting American fans with a comprehensive set of Avery's MGM shorts, to complete this task I had to scour the internet to find where desperate fans had uploaded copies of the cartoons to YouTube, DailyMotion and the like. They are out there if you look.

I watched these in chronological order and have written out a few remarks for all of them. Some are absolutely brilliant, some are run-of-the-mill but elevated briefly by a great gag or two, only a few are terribly bland and redundant. My particular recommendations will be highlighted in red.

[I will be covering his 1940's output soon but wanted to go ahead and post this overview to his 1950's work.]

See also: Tex Avery at Walter Lantz Productions (1954-1955)

Ventriloquist Cat (1950)

A cute premise but ultimately kind of forgettable Avery. In fact, after I watched several Avery’s for this I had literally forgotten everything about this one. I had to reference it again just to remind myself of the cleverish cat-throwing-his-voice-for-the-dog premise, which is basically Bad Luck Blackie with a special whistle. It would go on to be completely remade 7 years later in CinemaScope as Cat’s Meow.

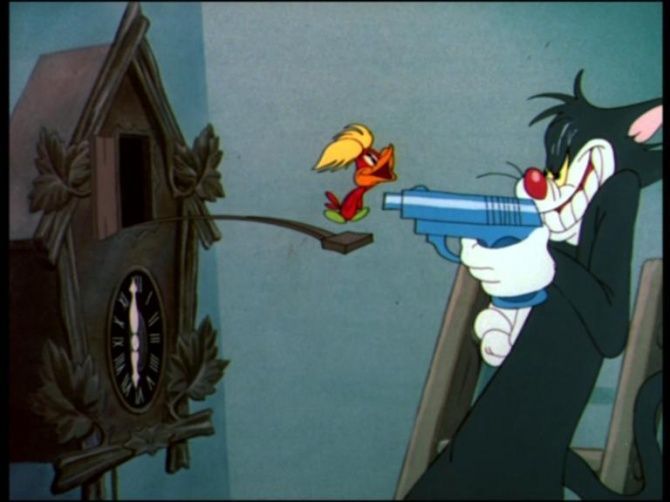

The Cuckoo Clock (1950)

I love the existential angst of the voice-over narration and then the ambiguous ending (did a cartoon finally bite it?). The little-guy-beats-up-big-guy theme was a favorite of Avery and would be seen a few times over (it’s basically what makes Droopy who he is), and even though it doesn’t offer me the same laughs-per-minute ratio as something like Magical Maestro, I am still really fond of this cartoon. The recurring motif of the injured appendage with that violin noise is gold.

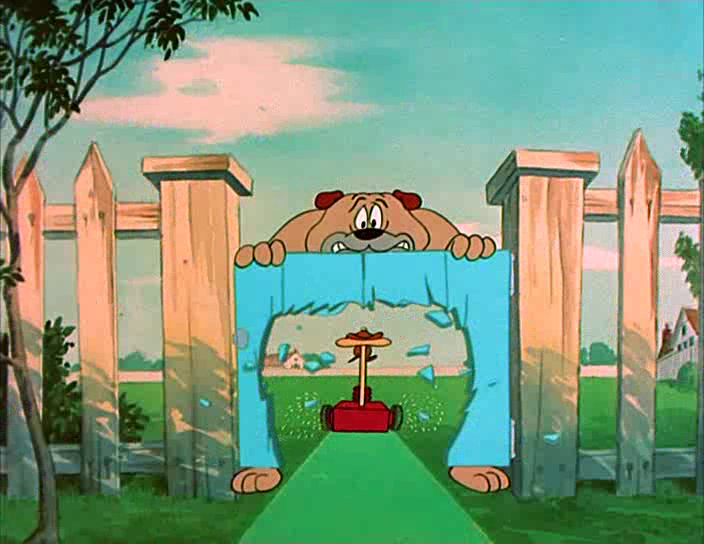

Garden Gopher (1950)

Run-of-the-mill Avery with Spike the dog battling a belligerent gopher. A few laughs but very minor Avery.

The Chump Champ (1950)

Spike vs. Droopy in feats of strength. A common scenario but I have some fondness for this one because I think the gags are strong and then the reversal at the end is a nice payoff. It also gives Droopy one of his best punchlines.

The Peachy Cobbler (1950)

Just a collection of tiny-elves-fixing-shoes gags. It is surprisingly endearing and the running joke with the roller skate speeding by and splashing shoe polish on the nice dress shoe is classic. This one grows on you because it is so good-natured, a nice turn for Avery.

Cock-a-Doodle Dog (1951)

A run-of-the-mill Avery that steps above that just a bit for the reversal at the end. Even though Avery might play on the same theme in multiple shorts, he wasn’t afraid to flip the script on the trope.

Daredevil Droopy (1951)

This is Chump Champ in a circus. I just realized the one I saw had some "offensive" gags cut out so it works even less effectively and feels very much like a collection of barely associated vignettes.

Droopy’s Good Deed (1951)

Chump Champ in a boy scout camp. The dadaist anti-climax was pretty good, though.

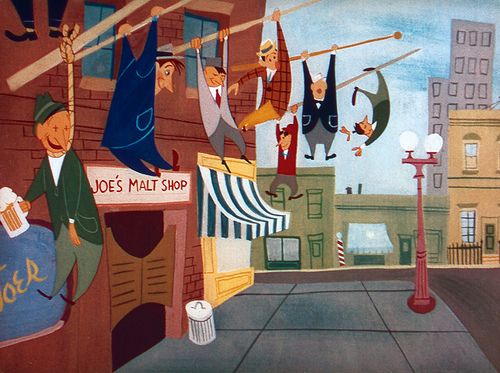

Symphony in Slang (1951)

This is one of those cartoons that was absolutely inevitable, and it is quite fitting that Avery went there (presumably first, I don’t know and frankly, don’t care). The premise is a guy who gets to heaven and starts recalling his life but the gatekeeper can’t understand the guy because he’s speaking in slang. The whole movie then becomes a brilliant deconstruction of American lingo and a literal expression of common phrases, beginning with the more overt slang (“I couldn’t cut the mustard”) and then subtly gets into turns of phrase that everyone pretty much says (“I drank a cocktail”, “I carried on”, etc.). It sounds like a premise that would work better on paper than on-screen, but Avery keeps things moving and ends up stringing enough phrases together where you have no idea what is coming next or how he can keep it up. He doesn’t let anything slip through unnoticed and is able to build up a great post-modern treatise on the insanity of language.

Car of Tomorrow (1951)

Avery did a few of these "...of Tomorrow" cartoons; this one is really just a collection of literal puns related to automobiles. Symphony in Slang did it all better and is much funnier. I found this one to be a bit of a clunker.

Droopy’s Double Trouble (1951)

A one-joke short with Droopy and his twin, Drippy, as butlers in charge of watching over a mansion. Droopy’s sensitive side comes through in this as he tries to show compassion to the down-on-his-luck Spike, not knowing that Drippy has been given the task of keeping strangers off the property. So, Drippy basically punishes Spike for his existence every time he sees him. Spike goes insane at the end. Features a great gag with the twin Droopys and two adjoining doorways.

Magical Maestro (1952)

An absolute masterpiece and my favorite Tex Avery cartoon. Those who feign offense at old cartoons that make any play on ethnic or cultural signifiers conveniently forget that the whole premise of a cartoon like this is a dog singing opera. Equality is found under the spell of magic stereotyping. But beyond all that is the ratatat barrage of gags that build into a crescendo of chaos. The way the rabbits keep popping up; the Dadaist attack on class and culture (the opera patron happens to have an anvil in his box seat); the hair in the gate. It is all pitch-perfect. This one shreds me every time.

One Cab’s Family (1952)

There are plenty of clever gags in this one as it relates to the anthropomorphism of the automobile. I’ll take this over Pixar’s Cars any day of the week, both as entertainment and as social commentary. And it’s only 6 minutes long. Not top tier Avery but still very enjoyable.

Rock-a-Bye Bear (1952)

One of the Spike as hero cartoons where some unnamed dog forces Spike to volunteer for a job that gets him out of the pound. The whole scenario is built around this other dog torturing Spike to get the hibernating bear (who seems so sensitive to noise) to wake up and beat Spike up/fire him. In true Avery fashion, each gag is a way to bring pain and force Spike to shout out. The cartoon is funny by itself but it sort of becomes obsolete after watching the superior Deputy Droopy, which borrows the same basic structure (and even a couple of gags) but doubles the zaniness and hilarity. But, to its credit, Rock-a-Bye Bear does have a fantastic final reversal. Also, I love Spike jaunty snow-shoe walk up the driveway after he gets the job.

Little Johnny Jet (1953)

A little bit of a One Cab’s Family retread with airplanes instead of cars (hey Disney, there’s an original idea!), with the kid being a jet instead of a hotrod. Apart from some light humor at the anthropomorphic airplane setup, this really doesn’t feel like an Avery comedy until the airplane race.

T.V. of Tomorrow (1953)

The only thing that keeps this from becoming a completely lifeless retread of Car of Tomorrow is Avery’s deep-seated annoyance at the proliferation of TV; this one has a much more cynical undertone than the other "...of Tomorrow" shorts. It still falls mostly flat for me, with the one exception being a fantastic joke with a character showing off the variety of channels (the same western TV show is playing on every channel) before going to a first run theater where the movie turns out to be the same western from TV. A great gag in a forgettable cartoon.

The Three Little Pups (1953)

More jokes on television as the 3 Little Pigs story gets revisited with Droopy housing the other dogs in his brick and steel home so they can watch TV. Run-of-the-mill but still pretty enjoyable.

Drag-a-Long Droopy (1954)

Western-themed Droopy cartoon where Droopy is a sheep-herder and the wolf is a cow herder and they battle over the land. Several clever gags keep this one moving along rapidly. I especially like the shootout.

Billy Boy (1954)

Avery has some fun with the animal-who-eats-anything premise: in this one, a goat who just lawnmows across the landscape to the chagrin of a stuttering farmer. The funniest image is the goat being tied inexplicably to a kite; the funniest gag is the goat being set in front of a railroad track to eat his way to California.

Homesteader Droopy (1954)

Another western-themed droopy that finds some pretty good laughs with an automatic homesteader kit and a mounted moose head. I enjoyed the anachronistic humor and the play on the western movie cliché “It’s the law of the west.” Also a great moment with the wagon circling itself and the Indians becoming merry-go-round riders.

The Farm of Tomorrow (1954)

A nice joke with the toaster-like incubator and a couple of good visual puns at the end can’t make up for a lifeless premise on its last legs. A total bore. Thankfully, this is the final of the “…of Tomorrow” cartoons.

The Flea Circus (1954)

A flea circus falls apart after a dog walks in. It is unique in Avery’s collection for being more strictly narrative-driven than a gag vehicle, though the narrative is still pretty thin. It is a cute little cartoon that doesn’t give much beyond a couple of light chuckles, though its good-natured charm is enough to keep it from being a total bore.

Dixieland Droopy (1954)

What begins as a fairly harmless and humorous story of a dog trying to play his Dixieland record while he pretends to conduct the band turns into a fascinating comment on musical stardom: Droopy gets all the credit while the real band, the fleas living on his rear, are unknown. It also features a hilarious gag with an unorthodox musical toupee. Not a great cartoon but a fun one with a nice conceptual catch at the end.

Field and Scream (1955)

Taking the same tired, vignetted structure of the “…of Tomorrow” shorts and making it only slightly more amusing, Field and Scream doesn’t improve upon the hunting jokes of Lucky Ducky or include any of its self-reflexive brilliance. There is a nice bit with an elephant gun, but it is mostly a misfire.

The First Bad Man (1955)

Avery dreams up what prehistoric Texas might have been like and gives us the story of the first outlaw, Dinosaur Dan. It is a decent premise that doesn’t get carried quite as far as it should.

Deputy Droopy (1955, co-driected with Michael Lah)

Going back to his roots a little bit, Avery gives us another great cartoon in the “don’t wake the sleeping character” premise of Rock-a-Bye Bear. But, he also improves on that short by having two characters tortured by Droopy’s string of zany assaults. The two would-be robbers play off of each other as they argue and repeat their own mistakes and even switch heads at one point. The whole thing is comic chaos and the ending (which was easy to spot) becomes subverted by Avery’s refusal to end the joke until Droopy gets the final punchline.

Cellbound (1955, co-directed with Michael Lah)

This was one of my favorites as a kid and it still works quite well. After spending twenty years digging his way out of prison one spoonful at a time, Spike accidentally takes refuge inside the TV the prison warden gets as an anniversary present to his wife. With his bag of costumes, Spike must act out all the programs the Warden tries to watch.

Millionaire Droopy (1956)

A shot-for-shot remake of Wags to Riches (1949), this time in CinemaScope and produced by Hannah & Barbera. I’m not sure what the story is behind these two CinemaScope cartoons (contractual obligation, artistic burnout or both) but they don’t even look like Avery’s other MGM cartoons. The originals have a more delicate color scheme and interesting backgrounds while the CinemaScope shorts have bolder colors and the looser backgrounds that will become commonplace as American studio animation moves into the 60’s.

Cat’s Meow (1957)

Same as above: a shot-for-shot remake of Ventriloquist Cat (1950), this time in CinemaScope and produced by Hannah & Barbera. It was already one of Avery’s weaker cartoons so this offered me nothing. It was actually pretty depressing and feels nowhere near as lively as the original even though the audio may be the exact same.

I watched these in chronological order and have written out a few remarks for all of them. Some are absolutely brilliant, some are run-of-the-mill but elevated briefly by a great gag or two, only a few are terribly bland and redundant. My particular recommendations will be highlighted in red.

[I will be covering his 1940's output soon but wanted to go ahead and post this overview to his 1950's work.]

See also: Tex Avery at Walter Lantz Productions (1954-1955)

Tex Avery at MGM, part 2 (1950-1957)

A cute premise but ultimately kind of forgettable Avery. In fact, after I watched several Avery’s for this I had literally forgotten everything about this one. I had to reference it again just to remind myself of the cleverish cat-throwing-his-voice-for-the-dog premise, which is basically Bad Luck Blackie with a special whistle. It would go on to be completely remade 7 years later in CinemaScope as Cat’s Meow.

The Cuckoo Clock (1950)

I love the existential angst of the voice-over narration and then the ambiguous ending (did a cartoon finally bite it?). The little-guy-beats-up-big-guy theme was a favorite of Avery and would be seen a few times over (it’s basically what makes Droopy who he is), and even though it doesn’t offer me the same laughs-per-minute ratio as something like Magical Maestro, I am still really fond of this cartoon. The recurring motif of the injured appendage with that violin noise is gold.

Garden Gopher (1950)

Run-of-the-mill Avery with Spike the dog battling a belligerent gopher. A few laughs but very minor Avery.

The Chump Champ (1950)

Spike vs. Droopy in feats of strength. A common scenario but I have some fondness for this one because I think the gags are strong and then the reversal at the end is a nice payoff. It also gives Droopy one of his best punchlines.

The Peachy Cobbler (1950)

Just a collection of tiny-elves-fixing-shoes gags. It is surprisingly endearing and the running joke with the roller skate speeding by and splashing shoe polish on the nice dress shoe is classic. This one grows on you because it is so good-natured, a nice turn for Avery.

Cock-a-Doodle Dog (1951)

A run-of-the-mill Avery that steps above that just a bit for the reversal at the end. Even though Avery might play on the same theme in multiple shorts, he wasn’t afraid to flip the script on the trope.

Daredevil Droopy (1951)

This is Chump Champ in a circus. I just realized the one I saw had some "offensive" gags cut out so it works even less effectively and feels very much like a collection of barely associated vignettes.

Droopy’s Good Deed (1951)

Chump Champ in a boy scout camp. The dadaist anti-climax was pretty good, though.

Symphony in Slang (1951)

This is one of those cartoons that was absolutely inevitable, and it is quite fitting that Avery went there (presumably first, I don’t know and frankly, don’t care). The premise is a guy who gets to heaven and starts recalling his life but the gatekeeper can’t understand the guy because he’s speaking in slang. The whole movie then becomes a brilliant deconstruction of American lingo and a literal expression of common phrases, beginning with the more overt slang (“I couldn’t cut the mustard”) and then subtly gets into turns of phrase that everyone pretty much says (“I drank a cocktail”, “I carried on”, etc.). It sounds like a premise that would work better on paper than on-screen, but Avery keeps things moving and ends up stringing enough phrases together where you have no idea what is coming next or how he can keep it up. He doesn’t let anything slip through unnoticed and is able to build up a great post-modern treatise on the insanity of language.

Car of Tomorrow (1951)

Avery did a few of these "...of Tomorrow" cartoons; this one is really just a collection of literal puns related to automobiles. Symphony in Slang did it all better and is much funnier. I found this one to be a bit of a clunker.

Droopy’s Double Trouble (1951)

A one-joke short with Droopy and his twin, Drippy, as butlers in charge of watching over a mansion. Droopy’s sensitive side comes through in this as he tries to show compassion to the down-on-his-luck Spike, not knowing that Drippy has been given the task of keeping strangers off the property. So, Drippy basically punishes Spike for his existence every time he sees him. Spike goes insane at the end. Features a great gag with the twin Droopys and two adjoining doorways.

Magical Maestro (1952)

An absolute masterpiece and my favorite Tex Avery cartoon. Those who feign offense at old cartoons that make any play on ethnic or cultural signifiers conveniently forget that the whole premise of a cartoon like this is a dog singing opera. Equality is found under the spell of magic stereotyping. But beyond all that is the ratatat barrage of gags that build into a crescendo of chaos. The way the rabbits keep popping up; the Dadaist attack on class and culture (the opera patron happens to have an anvil in his box seat); the hair in the gate. It is all pitch-perfect. This one shreds me every time.

One Cab’s Family (1952)

There are plenty of clever gags in this one as it relates to the anthropomorphism of the automobile. I’ll take this over Pixar’s Cars any day of the week, both as entertainment and as social commentary. And it’s only 6 minutes long. Not top tier Avery but still very enjoyable.

Rock-a-Bye Bear (1952)

One of the Spike as hero cartoons where some unnamed dog forces Spike to volunteer for a job that gets him out of the pound. The whole scenario is built around this other dog torturing Spike to get the hibernating bear (who seems so sensitive to noise) to wake up and beat Spike up/fire him. In true Avery fashion, each gag is a way to bring pain and force Spike to shout out. The cartoon is funny by itself but it sort of becomes obsolete after watching the superior Deputy Droopy, which borrows the same basic structure (and even a couple of gags) but doubles the zaniness and hilarity. But, to its credit, Rock-a-Bye Bear does have a fantastic final reversal. Also, I love Spike jaunty snow-shoe walk up the driveway after he gets the job.

Little Johnny Jet (1953)

A little bit of a One Cab’s Family retread with airplanes instead of cars (hey Disney, there’s an original idea!), with the kid being a jet instead of a hotrod. Apart from some light humor at the anthropomorphic airplane setup, this really doesn’t feel like an Avery comedy until the airplane race.

T.V. of Tomorrow (1953)

The only thing that keeps this from becoming a completely lifeless retread of Car of Tomorrow is Avery’s deep-seated annoyance at the proliferation of TV; this one has a much more cynical undertone than the other "...of Tomorrow" shorts. It still falls mostly flat for me, with the one exception being a fantastic joke with a character showing off the variety of channels (the same western TV show is playing on every channel) before going to a first run theater where the movie turns out to be the same western from TV. A great gag in a forgettable cartoon.

The Three Little Pups (1953)

More jokes on television as the 3 Little Pigs story gets revisited with Droopy housing the other dogs in his brick and steel home so they can watch TV. Run-of-the-mill but still pretty enjoyable.

Drag-a-Long Droopy (1954)

Western-themed Droopy cartoon where Droopy is a sheep-herder and the wolf is a cow herder and they battle over the land. Several clever gags keep this one moving along rapidly. I especially like the shootout.

Billy Boy (1954)

Avery has some fun with the animal-who-eats-anything premise: in this one, a goat who just lawnmows across the landscape to the chagrin of a stuttering farmer. The funniest image is the goat being tied inexplicably to a kite; the funniest gag is the goat being set in front of a railroad track to eat his way to California.

Homesteader Droopy (1954)

Another western-themed droopy that finds some pretty good laughs with an automatic homesteader kit and a mounted moose head. I enjoyed the anachronistic humor and the play on the western movie cliché “It’s the law of the west.” Also a great moment with the wagon circling itself and the Indians becoming merry-go-round riders.

The Farm of Tomorrow (1954)

A nice joke with the toaster-like incubator and a couple of good visual puns at the end can’t make up for a lifeless premise on its last legs. A total bore. Thankfully, this is the final of the “…of Tomorrow” cartoons.

The Flea Circus (1954)

A flea circus falls apart after a dog walks in. It is unique in Avery’s collection for being more strictly narrative-driven than a gag vehicle, though the narrative is still pretty thin. It is a cute little cartoon that doesn’t give much beyond a couple of light chuckles, though its good-natured charm is enough to keep it from being a total bore.

Dixieland Droopy (1954)

What begins as a fairly harmless and humorous story of a dog trying to play his Dixieland record while he pretends to conduct the band turns into a fascinating comment on musical stardom: Droopy gets all the credit while the real band, the fleas living on his rear, are unknown. It also features a hilarious gag with an unorthodox musical toupee. Not a great cartoon but a fun one with a nice conceptual catch at the end.

Field and Scream (1955)

Taking the same tired, vignetted structure of the “…of Tomorrow” shorts and making it only slightly more amusing, Field and Scream doesn’t improve upon the hunting jokes of Lucky Ducky or include any of its self-reflexive brilliance. There is a nice bit with an elephant gun, but it is mostly a misfire.

The First Bad Man (1955)

Avery dreams up what prehistoric Texas might have been like and gives us the story of the first outlaw, Dinosaur Dan. It is a decent premise that doesn’t get carried quite as far as it should.

Deputy Droopy (1955, co-driected with Michael Lah)

Going back to his roots a little bit, Avery gives us another great cartoon in the “don’t wake the sleeping character” premise of Rock-a-Bye Bear. But, he also improves on that short by having two characters tortured by Droopy’s string of zany assaults. The two would-be robbers play off of each other as they argue and repeat their own mistakes and even switch heads at one point. The whole thing is comic chaos and the ending (which was easy to spot) becomes subverted by Avery’s refusal to end the joke until Droopy gets the final punchline.

Cellbound (1955, co-directed with Michael Lah)

This was one of my favorites as a kid and it still works quite well. After spending twenty years digging his way out of prison one spoonful at a time, Spike accidentally takes refuge inside the TV the prison warden gets as an anniversary present to his wife. With his bag of costumes, Spike must act out all the programs the Warden tries to watch.

Millionaire Droopy (1956)

A shot-for-shot remake of Wags to Riches (1949), this time in CinemaScope and produced by Hannah & Barbera. I’m not sure what the story is behind these two CinemaScope cartoons (contractual obligation, artistic burnout or both) but they don’t even look like Avery’s other MGM cartoons. The originals have a more delicate color scheme and interesting backgrounds while the CinemaScope shorts have bolder colors and the looser backgrounds that will become commonplace as American studio animation moves into the 60’s.

Cat’s Meow (1957)

Same as above: a shot-for-shot remake of Ventriloquist Cat (1950), this time in CinemaScope and produced by Hannah & Barbera. It was already one of Avery’s weaker cartoons so this offered me nothing. It was actually pretty depressing and feels nowhere near as lively as the original even though the audio may be the exact same.

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

Forrest Gump (1994) and the Subversion of American Exceptionalism

Forrest Gump is the story of a blank slate of a man who finds himself passing through many essential and non-essential moments in 1960’s and 70’s America. I describe him as a blank slate because he is very simply motivated and a character that the audience will cast their own meaning upon because of his simplicity. Though Forrest has a low IQ and is generally thought to be stupid, he is guileless and loyal, naïve and, in many ways, innocent. His innocence is not born from his ignorance, however: it is born from his loyalty. He takes people at their word.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)