Forrest Gump is the story of a blank slate of a man who finds himself passing through many essential and non-essential moments in 1960’s and 70’s America. I describe him as a blank slate because he is very simply motivated and a character that the audience will cast their own meaning upon because of his simplicity. Though Forrest has a low IQ and is generally thought to be stupid, he is guileless and loyal, naïve and, in many ways, innocent. His innocence is not born from his ignorance, however: it is born from his loyalty. He takes people at their word.

There is a key moment after Lieutenant Dan has lost his legs that he pulls Forrest to the floor one night in the hospital and accuses Forrest of ruining his destiny. Lt. Dan even ponders, “I was Lieutenant Dan Taylor.” Forrest’s response: “You’re still Lieutenant Dan.” His response is simple and revealing. It seems Dan reads something more into it and it is easy for the audience to read something greater into it as well. He has his life and his identity. His perceived destiny was to either rise in rank as part of a military career after the war or to die in battle. Instead, he emerges from the war a paraplegic because Forrest refused to leave him lying wounded on the battlefield. Forrest’s response is innocent. Why wouldn’t Lieutenant Dan be Lieutenant Dan? It could be ignorance or, it could be Forrest loves Lieutenant Dan and can’t understand why he is so confused about his destiny. To Forrest, if Lt. Dan is alive then he has not fulfilled his destiny. Simple as that.

|

| "You're still Lieutenant Dan," Forrest innocently tells Dan in a moment of existential crisis. |

Forrest is of the

moment, living life as it happens.

The only schemes that he ever puts in place are directly tied to his own

loyalty to friends: his commitment to Jenny and his commitment to Bubba. His commitment to Jenny is not so much

a scheme as it is a desire, a desire entirely contingent upon her because he

has done everything necessary for their relationship to exist. If she asked him to do something for her,

he would do it. His commitment to

Bubba weighs on him because it requires an inordinate giving of himself in the

pursuit of maintaining his promise to his friend, and also requires at least

some planning on his part as to acquiring the money to fund it and meeting the

people necessary to fulfill it.

All of the accoutrements

of Forrest’s success (fame, wealth, being a witness to history, having met with

celebrities) are things he never sought and therefore

they are things he never clings to or finds satisfaction in having. This is essential to understanding Forrest

Gump because it is what makes

Forrest distinctive from the other characters in the film. If Forrest cared about having wealth

then the fact that he lucked into wealth would become a statement about wealth

and how one might attain it.

Instead, the way his wealth is attained is a statement about

Forrest. Not because he is simple-minded,

but because he found it accidentally in his attempt to make good on a promise. Making money was never the promise he

made to Bubba; buying a shrimp boat was.

|

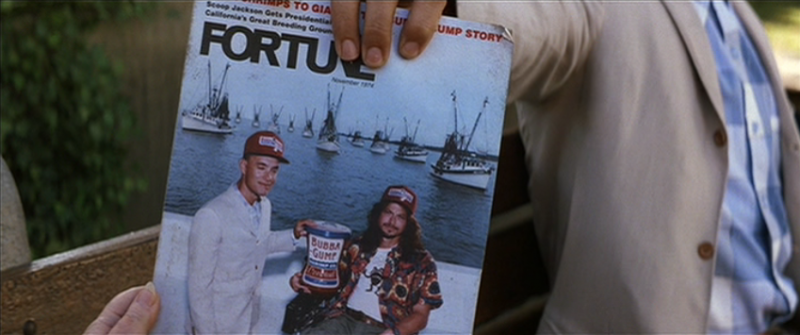

| Forrest's guilelessness is evident when he asks a listener if they want to see what Lieutenant Dan looks like. He does not offer this as proof of his story's validity. |

By establishing themes of fate and chance, Zemeckis is painting a character larger than America, larger than the ideals held up as symbolic of the country. Freedom, democracy, progression, wealth, success: Forrest brushes up against all these ideals but never clings to any as a means of salvation. He is not exceptional because he is American. It is his mother, Jenny, Bubba, Lt. Dan and, much later, Little Forrest who Forrest will give himself for, not a flag or an ideal. This personal loyalty throws him into such contrast from the changing American landscape of the 60's and 70's, a society growing less interested in personal loyalty and more interested politically in either the reification of conservative traditionalism or liberal progression, more interested culturally in passing entertainment. Zemeckis posits that Forrest Gump is not a character unique to America, he is a character unique in America.

Contrary to conventional

Hollywood formulas, Forrest Gump

is not a film about Forrest learning to stand up for himself and bravely show

down those who would abuse or exploit him. He accepts what comes to him, partially through ignorance,

partially through naïveté, and partially through a belief in God ordering his

steps. He doesn’t question his

destiny because he doesn’t believe destiny is something that is

questioned. Consequently, this

leads to Forrest being exploited by social institutions either because of his

IQ or his guilelessness. He does

not realize he is being exploited by his country, by his college, or by a ping

pong paddle company. He accepts

them passively. He doesn’t understand

or care about politics and doesn’t judge people based on arbitrary

prejudices. When desegregation is

happening at his school, he picks up a book dropped by one of the black

students as she walks into the building.

He sees a person who dropped a book, a need that can be filled. He picks it up and hands it to

her. This is not a political

statement; it is not a grab for attention. It is a person acting purely in response to another

person. It is passive in that it

is not consciously political.

It seems that this has

been a major sticking point for many contemporary critics, who despise the

movie for allowing such a passive character to wander through the liberal

darlings of feminism, the counter-culture, the peace movement and Civil Rights

without understanding anything beyond a very broad external. The depiction of the Vietnam War, for

instance, has been oft cited for its lack of depth and complexity. What fails to be grasped is that

Vietnam (and indeed, all the events depicted in the film) are seen through

Forrest’s point-of-view. Because

of this, they lack depth and complexity because he does not see it. He sees what people do and hears what

people say. This is what he

remembers.

Forrest Gump is not as openly satirical as similar cinematic

picaresques O Lucky Man!

(Lindsay Anderson, 1973) or Being There (Hal Ashby, 1979).

This is primarily because Robert Zemeckis likes the character of Forrest

and he builds the narrative lovingly around him so as to keep his voice

humanistically authoritative.

Though, theoretically he is an unreliable narrator because of his low IQ

and passivity, he turns out to be the most reliable of narrators because he has no

desire to lie to another human being, no hidden motives besides simply telling his stories to people. The audience,

being privy to both the narration of Forrest’s stories and the visual of his

memory get to see where the narrational discrepancies lie (investing in a

“fruit company” that turns out to be Apple computers, for instance) and see

that, though he has misrepresented something, it reflects his childlike view of

the world. This is often where the humor

of the film emerges.

|

| Forrest's tender empathy is seen when he sits down with the boy he learns is his son. They watch "Bert and Ernie" together. |

If anything, Forrest

Gump’s emphasis on chance

skewers the determinism wrought by self-awareness. Forrest happens to pass through many events most Americans

would deem important. He passes through

them unawares, often because he happens upon them. When Forrest goes to China to play ping-pong he is aware of

the historical significance of the trip because people have told him, but that doesn’t resonate with him as

anything other than a strange aside.

He just wants to play ping-pong.

Forrest Gump also skewers American exceptionalism in that

Forrest’s jaunt through American history is arbitrary and random; it does not

occur through his hard-work and American determination to build a great life

for himself. Meeting a President

is just as interesting as being given a pair of running shoes, stumbling into a

Vietnam protest is as random as inventing a bumper sticker slogan. He finds no purpose in the things he

does, the places he has been or the things he has accomplished. They are memories, stories: if he were

proudly listing off his great achievements, we the audience would resist

him. Instead, we are free to find

meaning and significance in what he has done, though he himself will not join

us in seeing it. He does not tell

us what to think and why: we read into it our own histories, our own

prejudices, our own interests and politics. Forrest Gump symbolizes what we want him to symbolize and in

so doing, reveals our rootless quest for meaning to be just as arbitrary as a feather

being blown by a breeze and landing at the feet of an idiot. We would like to think ourselves more

advanced, more intelligent, more significant than that, but are we?

No comments:

Post a Comment