I can see the moment in Scorsese's career where he steps confidently into the role of a great director: the gun purchasing scene in Taxi Driver. Seen through the singular point of view of Travis as he eyes each gun, with a particularly beautiful pan across the .44, the salesman talks and talks about the benefits of every gun and we stay on Travis as he feels the gun in his hand, following his sightline out the window, across the city, over the freeway and to a couple of pedestrians milling about on the sidewalk several stories below. No click of an empty chamber. No comment about the scum. We have no clue where this is going or how far, but we know everything in this world is wrong and it is frightening to imagine what Travis may end up doing. When he points the gun out the window, the camera's lens is focused on the outside, not the gun. We feel his mind, even though we do not know it through narration.

|

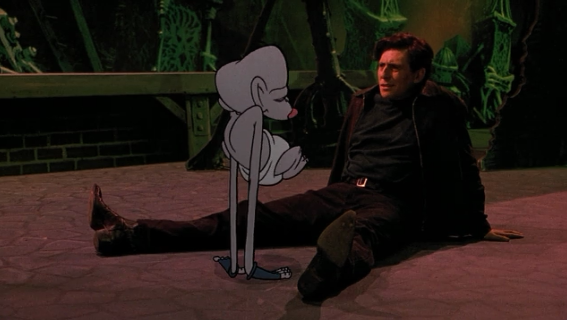

| Our hero, imagined: insulated with words, overlooking the city, violence brewing. A prophet of rage seeks for his voice. |