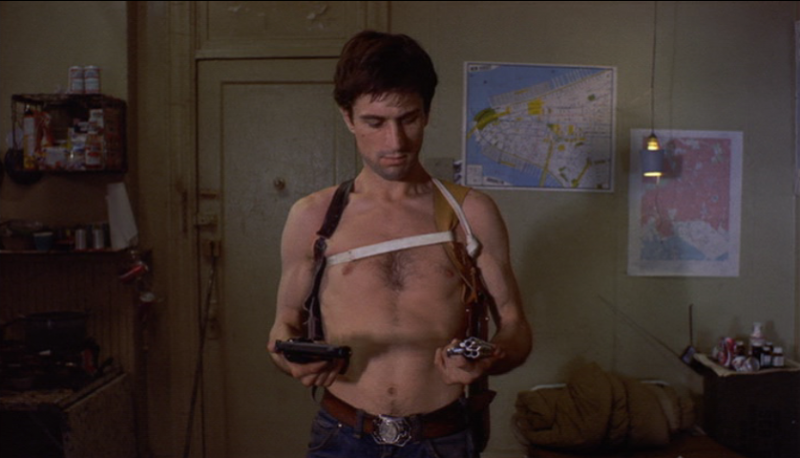

I can see the moment in Scorsese's career where he steps confidently into the role of a great director: the gun purchasing scene in Taxi Driver. Seen through the singular point of view of Travis as he eyes each gun, with a particularly beautiful pan across the .44, the salesman talks and talks about the benefits of every gun and we stay on Travis as he feels the gun in his hand, following his sightline out the window, across the city, over the freeway and to a couple of pedestrians milling about on the sidewalk several stories below. No click of an empty chamber. No comment about the scum. We have no clue where this is going or how far, but we know everything in this world is wrong and it is frightening to imagine what Travis may end up doing. When he points the gun out the window, the camera's lens is focused on the outside, not the gun. We feel his mind, even though we do not know it through narration.

|

| Our hero, imagined: insulated with words, overlooking the city, violence brewing. A prophet of rage seeks for his voice. |

|

| This is the only scene in the film in which "violence" appears sexy. |

|

| A strange moment where literally focusing on what is outside experientially links us to what is happening inside our protagonist. This is not a true POV, though it feels like it. |

|

| An expressionistic first image gives us a central visual metaphor and a hint of a lineage of savagery, the Viking ship cutting through the fog. As long as the ship is at sea, all is well. |

Travis isn't above it, he is shaped by it just as everyone else is. He neither ignores it nor embraces it. Somehow, that metaphorical sewage he bemoans fuels him to keep going even as it drives him mad with the most frighteningly calm rage. Does De Niro even raise his voice in this movie? I don't remember it. I remember a sick gleam in his eye when he talks to himself in the mirror. I remember the diplomatic apologies after he takes Betsy to the "medical film". Who is this person?

|

| De Niro's iconic scene -- often removed from context to become a symbol of cool self-assurance -- in context is a frightening moment of self-aggrandizement by a weak and unsure man. |

Bickle considers: perhaps he is clean enough to touch that which must not be touched, to step into the shoes of God and act to restore justice to the world, if only for one other person, if only in one tiny bedroom in a city of millions. Amazingly, he is not struck down. He is spared. There is no bullet left in the chamber for him, though he accepted it.

He makes it out alive and is hailed as a hero, continuing his life unencumbered by guilt or law. He can't make a career out of it, but he did help someone. Not just murdering the pimp that breaks Iris' commitment and allows her to find safety in her home, but that jolt of reality that breaks inertia, the jolt that breaks every illogical desire she might ever have to return to walking the gutters for $25 for 30 minutes.

What happens to him? It looks like he will glide on into the night, continuing to transport people from one side of the jungle to the other.

Taxi Driver is not about growth and development. This is not a life to be emulated. Bickle's actions are a testament, a warning. This is that jolt that breaks inertia. In the Old Testament, the wrath of God -- in addition to being a vessel of true and righteous judgment -- was always intended to bring those who were spared to repentance, if they had the eyes to see it. Maybe the tragedy in stories like this is that the lone wolf is easy to justify. He was alone, he was an insomniac, he saw too much, he didn't know enough people....he was rootless, restless, hopeless... For Scorsese and Schrader it is not that easy. They make no efforts to psychoanalyze Travis Bickle. He is no prophet, no holy man, certainly not God, but he is an angel of death. And we are left unsure if his wrath has yet been quenched. He may not look like much, but what should frighten us is that he looks a whole lot like anyone.

film journal 01.12.2014

No comments:

Post a Comment